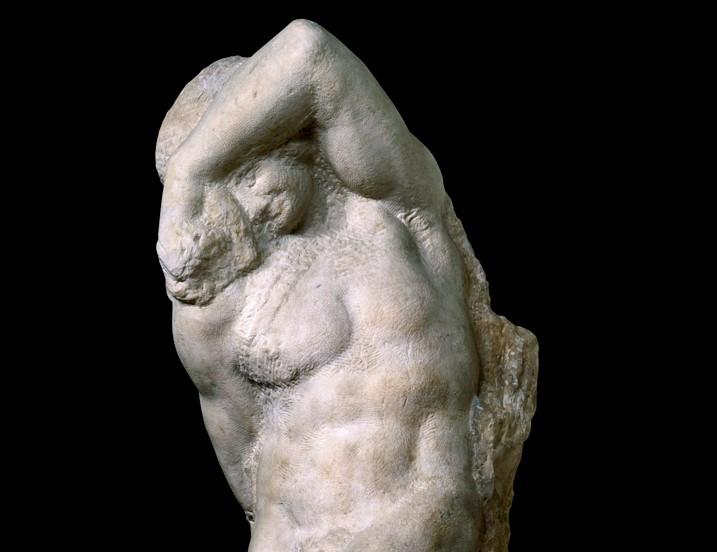

Our artistic traditions are full of wisdom. We can look to the past and, with curious minds and open hearts, absorb the lessons of our cultural history. The Italian Renaissance is filled with great stories that resulted in great art, and the story and art of Michelangelo are an enduring example.

Sistine Ceiling between 1508-1512 by Michelangelo. Fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican. Public Domain

|Updated: