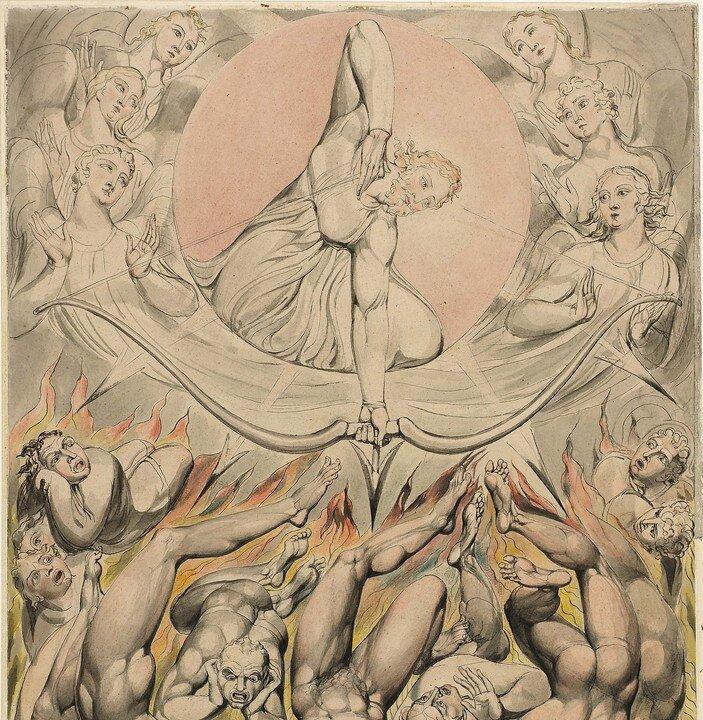

As we come close to the middle of 2020, I’m left asking “What else will happen?” It’s been an eventful year so far, to say the least. I’ve been thinking deeply about the events that have occurred this year, and I believe the time is ripe to reflect on ourselves and question what it means to be good human beings. I, myself, was encouraged to reflect when I came across the illustration by William Blake titled “The Casting of Rebel Angels Into Hell,” based on John Milton’s “Paradise Lost.”

John Milton and ‘Paradise Lost’

John Milton was a 17th-century English author, whose greatest work is “Paradise Lost,” an epic poem about the conflict between God and Satan and its effect on human beings. He wrote with the help of an assistant after going completely blind.The second edition of “Paradise Lost” was published in 1674 and contained 12 books, which included prose arguments defending the ways of God at the beginning of each book. According to the Poetry Foundation website: