It’s interesting how our vices lose strength when they are brought out into the open; they gain power when they’re hidden in the dark spaces of our spirit. I’ve been thinking a lot about what I see to be my own vices and how I should deal with them. I want to rid my heart and soul of my vices, but shame forces me to keep them hidden, where their strength only multiplies.

Confession and the Grace of God

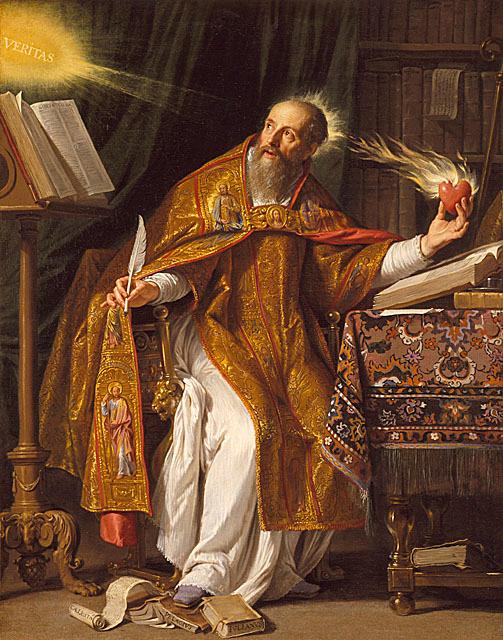

St. Augustine had a similar issue with his own vices. At one point, he famously prayed, “Lord give me chastity—but not yet.”In his book “The Confessions,” St. Augustine explores the soul’s struggle between virtue and vice. He begins every chapter with a prayer to God and confesses his own struggles with sins such as ambition, pride, and lust. In the end, he suggests that humbly confessing one’s imperfections to God is necessary for correcting one’s vices. Only God’s grace can help with overcoming sin.