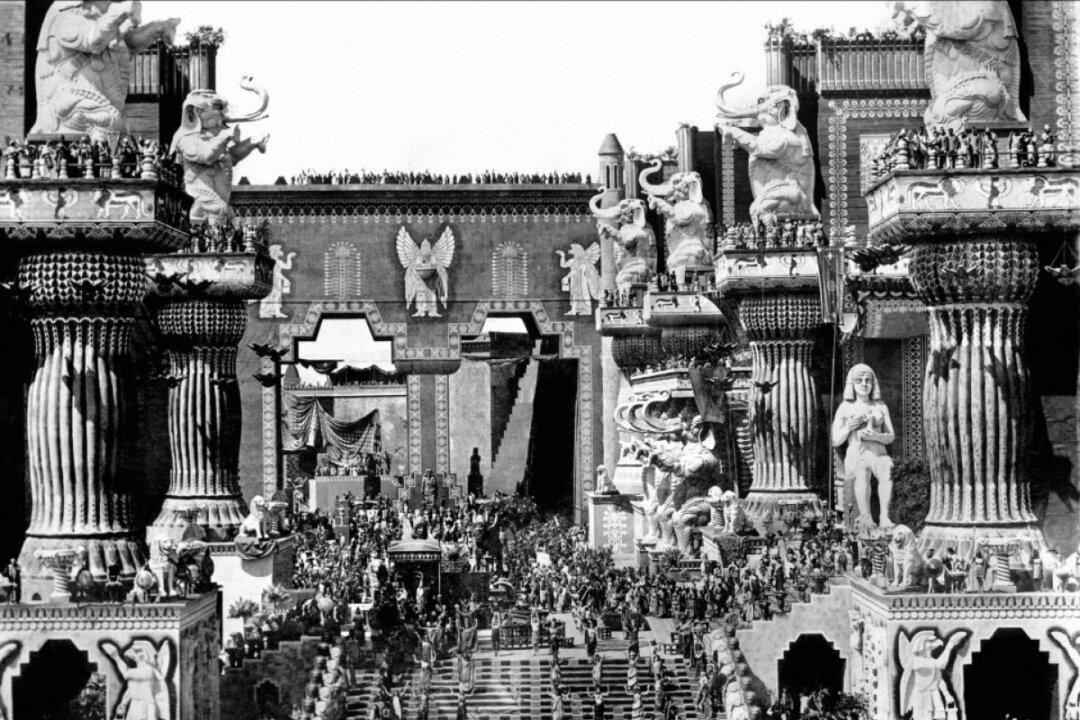

Everything about cinema’s first blockbuster, “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), seemed new: its three-hour running time, complex narrative, large cast of characters, and its powerful emotional effect on audiences.

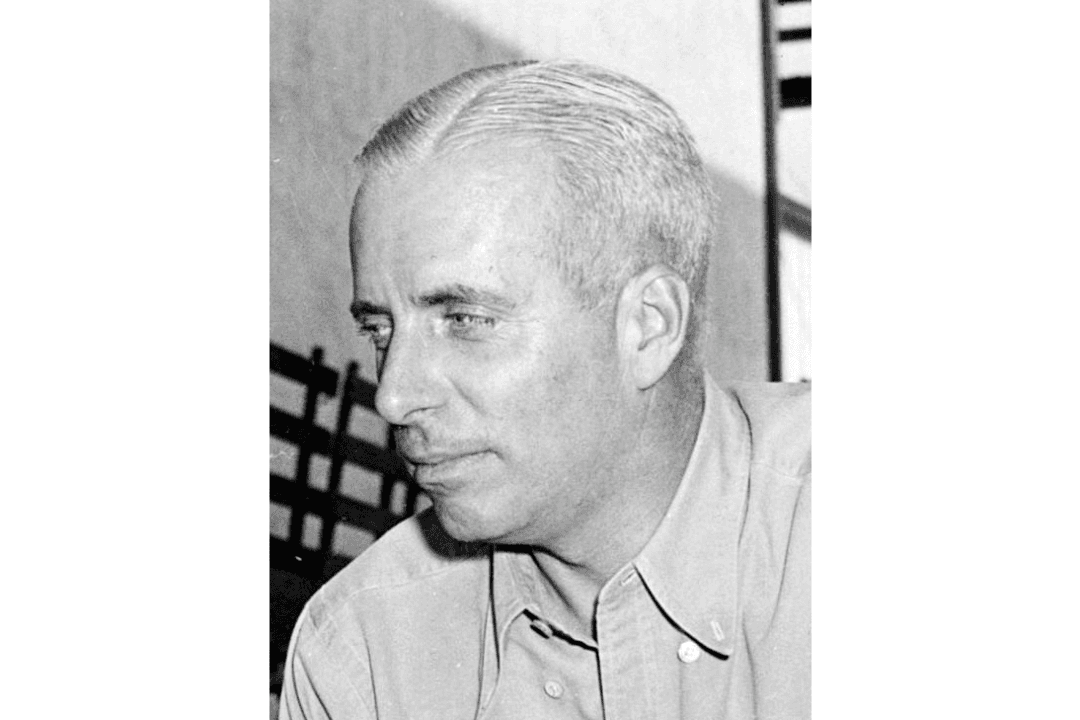

Its director, David Wark Griffith, was born in 1875, the son of a Kentucky farmer. A mediocre actor, he toured the country for years with ragtag theater troupes. He never hit it big, but he did gain a thorough knowledge of stagecraft, plays, and above all—audiences. In 1908, he fell into film directing almost by accident. In the over 450 short movies he cranked out for the Biograph company, he expanded the narrative and pictorial possibilities of film, pioneered new techniques like crosscutting and flashbacks, and set the stage for his Civil War epic.