Like a good many Christmas traditions and trappings, a fresh look at them may return luster to a dullness that can build up with time and custom. In fact, from a cultural perspective, such an exercise is part of the whole purpose of Christmas and the impending New Year.

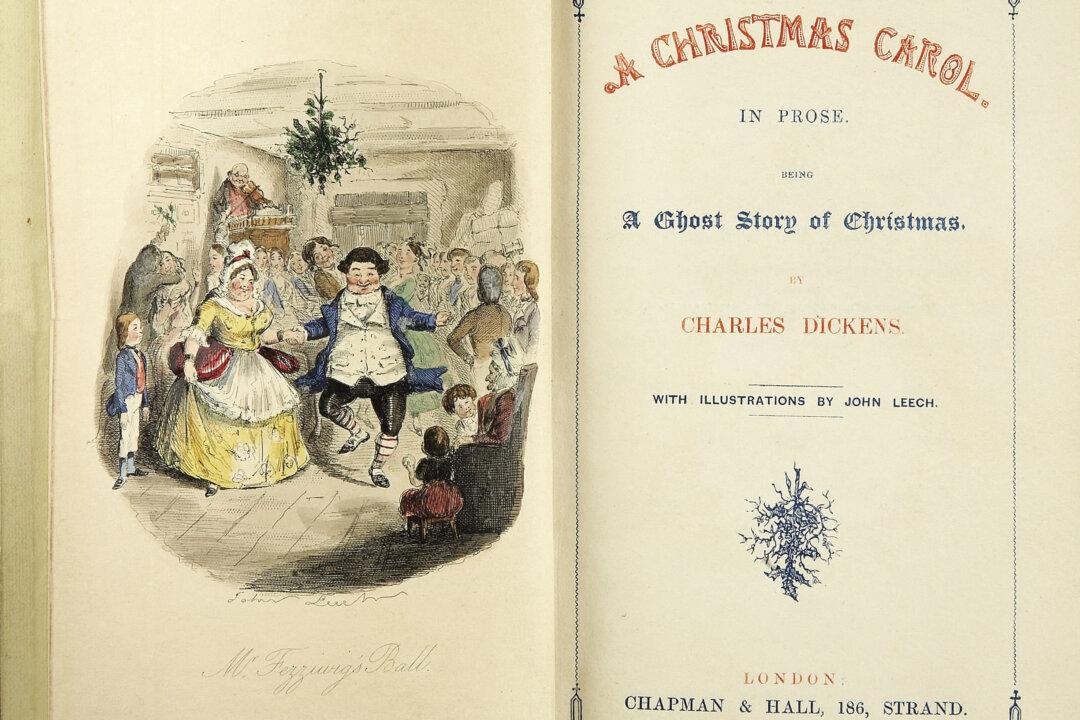

It’s a time to consider ourselves anew in a light of resolve and appreciation for our blessings. Serving as a means to accomplish this is a story that stands as largely unfamiliar, only because it is largely held as familiar: Charles Dickens’s 1843 masterpiece, “A Christmas Carol.”