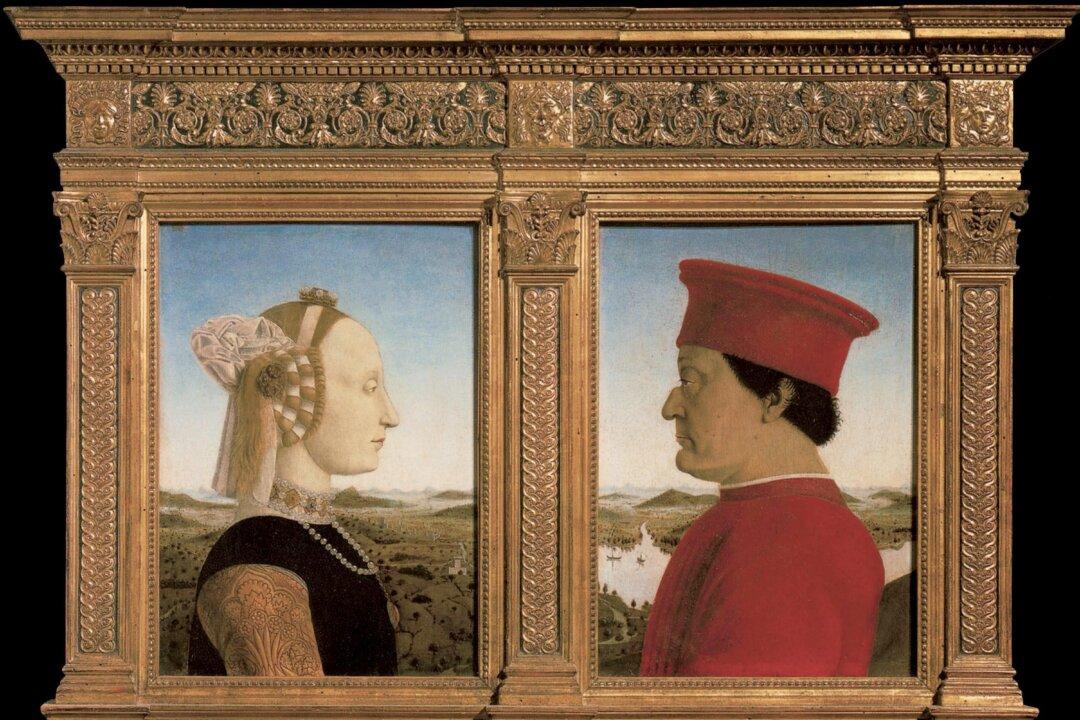

The double portraits of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza by Piero della Francesca in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, is an intriguing masterpiece by one of the greatest painters of the Italian Renaissance.

Portraits of Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro, circa 1473–1475, by Piero della Francesca. Oil on wood; 19 inches by 13 inches per panel. Uffizi Galleries. Public Domain