When the Circus Was the Only Show in Town

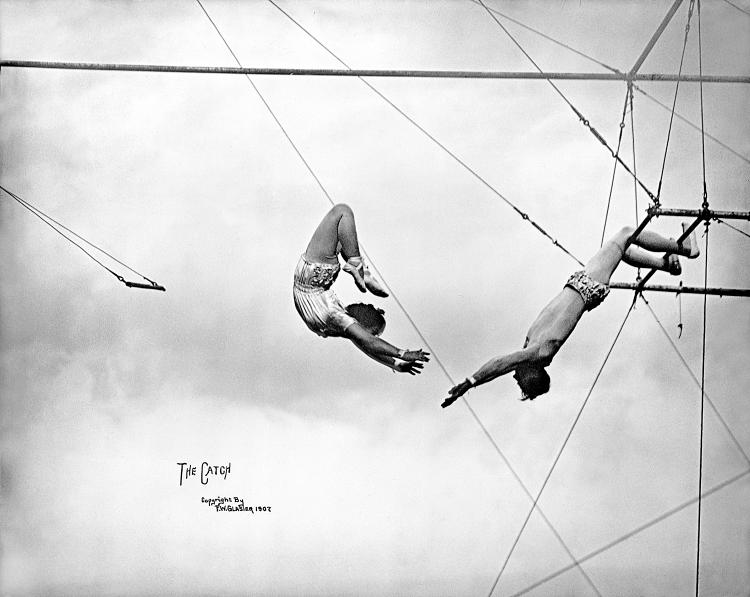

Long before movies, TV, and computers became part of daily life, young and old anxiously awaited the trains of the great circus companies, bringing the biggest and best of 19th-century entertainment.

|Updated: