When I was around 9 or 10 years old, my family was visiting my mom’s parents, who operated a dairy farm in Pennsylvania. The house owned by my grandparents was nearly 200 years old, and at night the shadows in the rooms, the dim-lit stairs, and the creaking floorboards often fired up ghosts in the imaginations of those of us in the younger set.

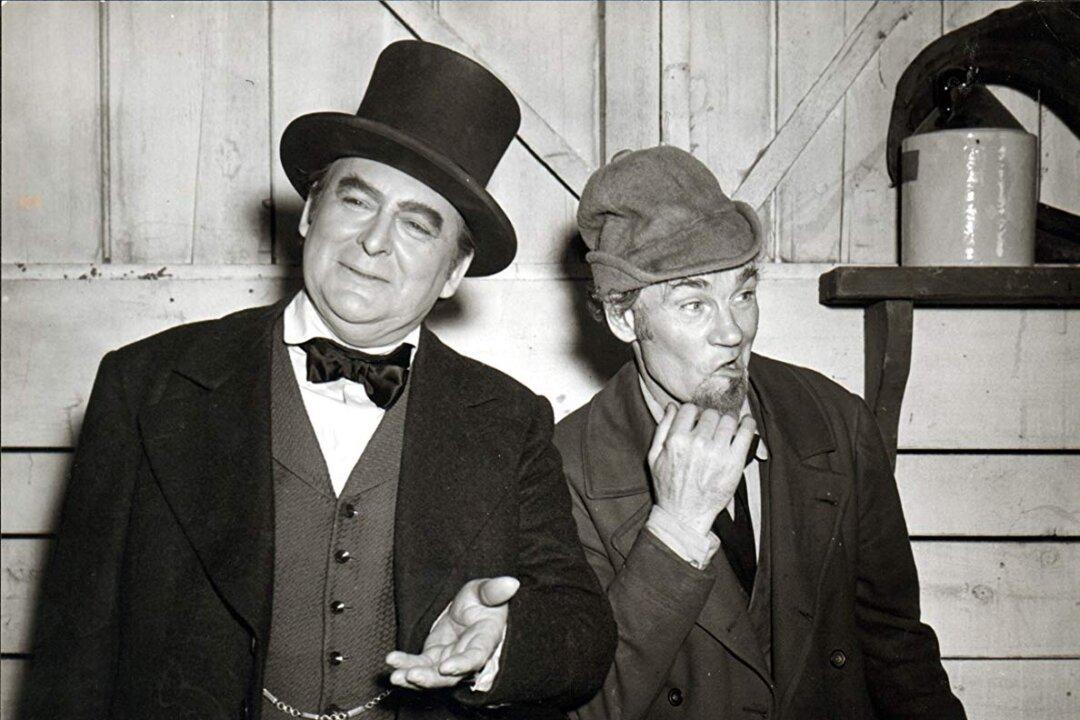

Those terrors doubled one evening after we watched a televised version of “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” the story of a New England farmer, Jabez Stone, who sells his soul to the Devil for seven years of prosperity. If memory serves, the show was in black-and-white, and it left me in bed that night staring into the darkness for what seemed an eternity, terrified to close my eyes and sleep.