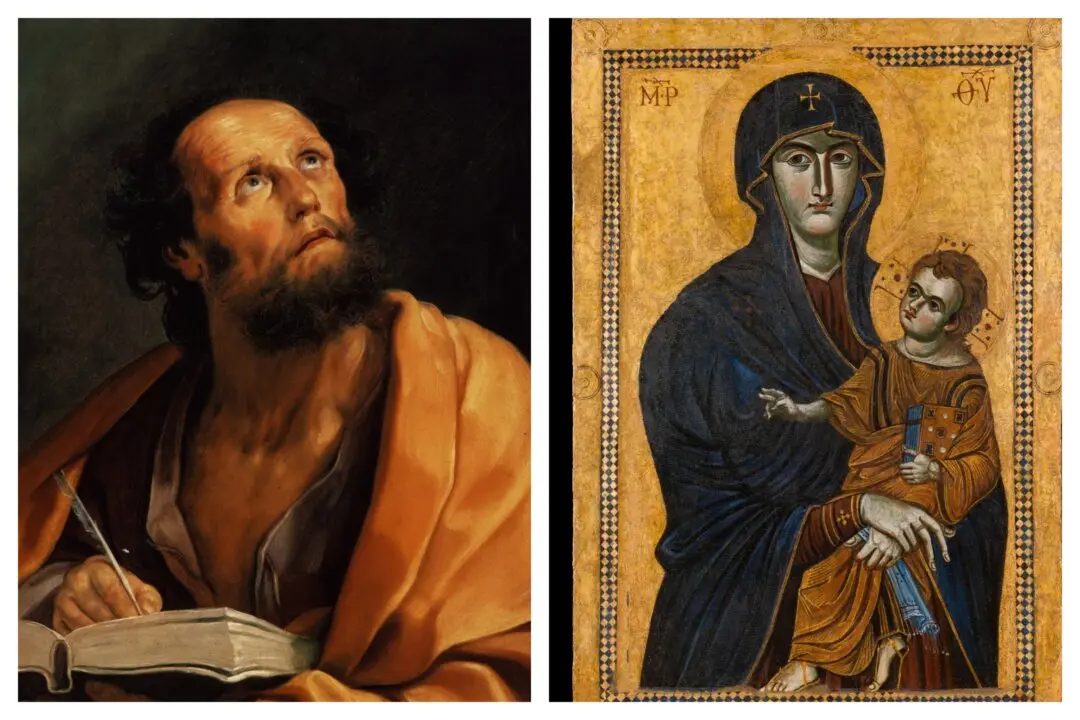

The reputation of St. Francis of Assisi as a nature lover often eclipses his identity as a writer in modern culture, and yet he is among the principal figures in Italian literature.

In his youth, St. Francis greatly admired the courtly love poetry and lifestyle of the troubadours; in his maturity, Francis embraced the title “Jugglers of God” (“Jongleurs de Dieu”) for himself and his first followers.