NEW YORK—If you’ve ever passed through Grand Central Terminal, Cathedral of St. John the Divine, or the municipal building at One Centre Street, you’ve unwittingly experienced the architectural artistry of Rafael Guastavino Sr. and his son Rafael Jr.

In fact, you’ve probably been in more Guastavino buildings than you know. Of the more than 1,000 significant projects the duo handled in the United States, more than 300 are or were located throughout New York City’s five boroughs, and many are open to the public.

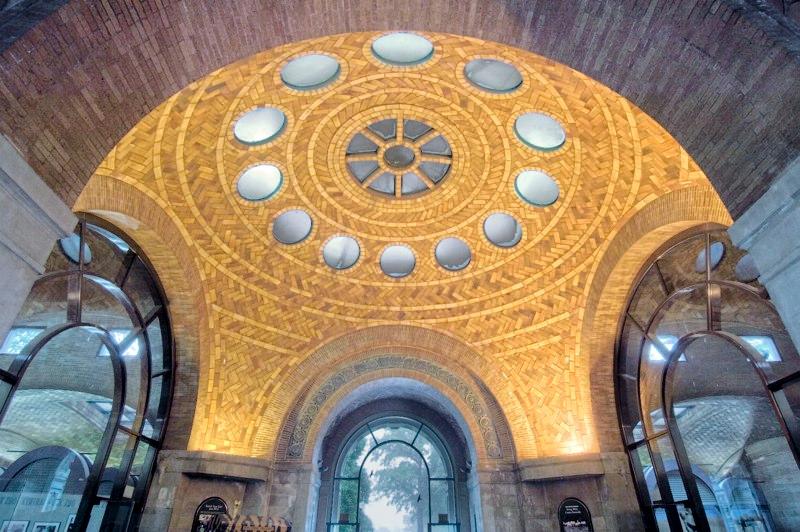

The father-and-son team created Byzantine and Gothic spaces whose beautifully tiled arches and vaults visually soar, filling the viewer with awe and confidence. Their greatest contributions to architecture were their innovations in thin-tile vaulting, a North African and Mediterranean technique that produces ceilings like eggshells—thin and surprisingly strong.

A new exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York explores the creativity and legacy of the Guastavinos through archival and contemporary photographs, technical drawings, and architectural components.

Immigration, Innovation

Guastavino Sr. studied architecture and construction in Barcelona, and eventually worked with leading American architects of the Beaux-Arts tradition. Finding his native Spain lacking in opportunities, he came to the United States in 1881 with his 8-year-old son in tow.

Here, they found themselves amid a building boom. Industrialization and urbanization created a huge building demand—as well as widespread fear of fires. At a time when most structures in the States were made of wood, Guastavino’s expertise in fireproof tile proved to be highly sought-after.

“By 1910, the Guastavinos were building 100 buildings at a time up and down the East Coast,” said MIT engineering professor John Ochsendorf, who co-curated the exhibit with architectural curator G. Martin Moeller Jr.

Together they obtained 24 patents, including one for Akoustolith, a porous building material that reduces echo—crucial for buildings that feature high, vaulted ceilings.

They used their patents aggressively, Ochsendorf said. If someone tried to copy a material or technique, they would take over the latecomer’s project—which partially explains why the Guastavinos were so prolific.

Blind Demolition

“Part of the reason for me as an engineer, why it’s important to raise awareness of this, is because this is our heritage,” Ochsendorf said. “He was able to do things we are only beginning to appreciate today. And if we don’t celebrate them, we’re going to lose them.”

As talented as the Guastavinos were, they were only known among a small circle of building professionals—the public had no clue who they were; craftsmen were largely anonymous compared to the better-known architectural firms they worked with.

Their relative anonymity, plus the public’s ignorance, led to many of their buildings being demolished to make way for newer, more modern ones.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission wasn’t created until 1965, two years after the original Penn Station—a Guastavino collaboration with architectural firm McKim, Mead, and White—was razed.

Neither father nor son was around to see this—Guastavino Jr. died in 1950.

Researchers at MIT’s Guastavino Project have initiated a geo-tagged map listing all known current and previously existing Guastavino sites. Exhibition curators are asking New Yorkers to send in possible locations that might have been missed.

I was excited to discover that one of the addresses, 238 W. 28th Street in Manhattan, shares a block with the Epoch Times office. According to the Guastavino Project map, it was formerly a fur merchants’ warehouse with a Guastavino water tower.

I rushed over to see what I had been missing, only to find that no building stands where 238 would be—only a parking lot offering parking to students of the Fashion Institute of Technology.

According to documents publicly available on the website for the Office of the City Register, the parcel of land was condemned in the 1960s and now is property of FIT. That’s about all I could conclude from the City Register website; decades-old paperwork, photocopied then scanned, made for extremely difficult reading.

Awareness and Revival

It’s astounding how quickly Beaux-Arts architecture faded out of use by the turn of the century.

“The knowledge was lost ... modernism comes along—sleek, modern, straight lines—there’s no room for a Guastavino vault in a rectilinear world,” Ochsendorf said.

“When everyone was so swept up with modernism, Guastavino ended up playing for the losing team. The irony, of course, is that the public loves the grand spaces of a hundred years ago and abhors the brutalist rectilinear buildings of the ’50s and ’60s. So Guastavino has the last laugh.”

Today, Ochsendorf hopes that through study and experimentation, Guastavino’s technique can be revived and put back into use.

He and Henry Louie, instructor at the International Masonry Institute, led a team of engineering students to create a large-scale replica of a Guastavino vault.

It, along with a time-lapse video of its creation, anchors the exhibit. Though only three tiles thick, it can support 30,000 pounds. Thanks to many hands and quick-drying plaster of paris, the replica was built in only three days.

As a member of the bricklayers’ union, Louie was sent to restore the Queensboro Bridge Underpass and Bridgemarket in 1998. He and the team were tasked with replacing loose tiles and cleaning the vaults, of which there are over 30.

“When we got to the last few vaults, big portions were missing and the roadway beams [from the bridge] were touching the vaults, and damaged them,” Louie recalled.

Louie’s colleague, stone mason Eugene “Gino” A. Marchese Jr., went to the library to study how Guastavino built the vaults. Through his guidance, the team lowered the vaults by 18 inches and restored the integrity of the structure.

Marchese passed away last month at age 64. If it weren’t for Marchese’s and Ochsendorf’s research, Louie said, the knowledge needed to restore such a structure probably would have slipped away.

Today, as the city faces aging infrastructure, the challenge of how to protect ourselves from climate change, and rising population, the idea of architectural permanence is again becoming relevant. The question is whether our society is willing to fund something as labor-intensive and costly as a Guastavino project for the future.

Palaces for the People

March 26–Sept. 7

Museum of the City of New York

1220 Fifth Ave. (at 103rd St.)

$6–$10

mcny.org

On April 15–17, families are invited to participate in a thin-tile vault building experiment. Other public programs associated with the exhibit will be announced on the museum website.