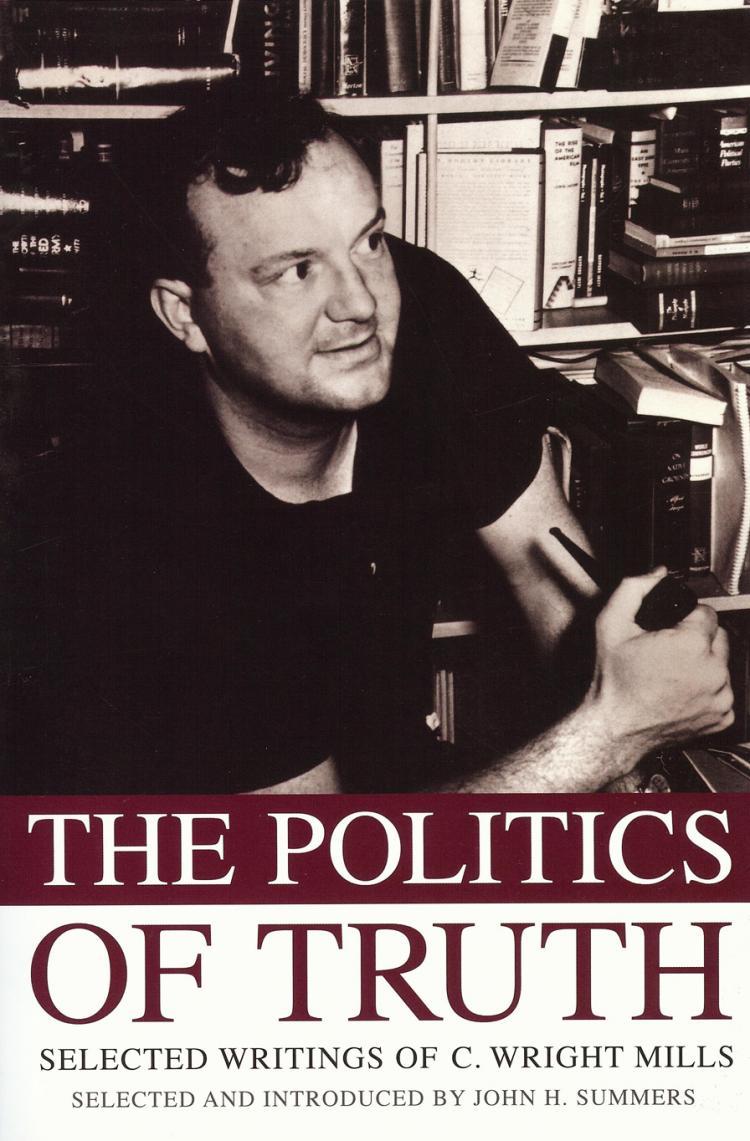

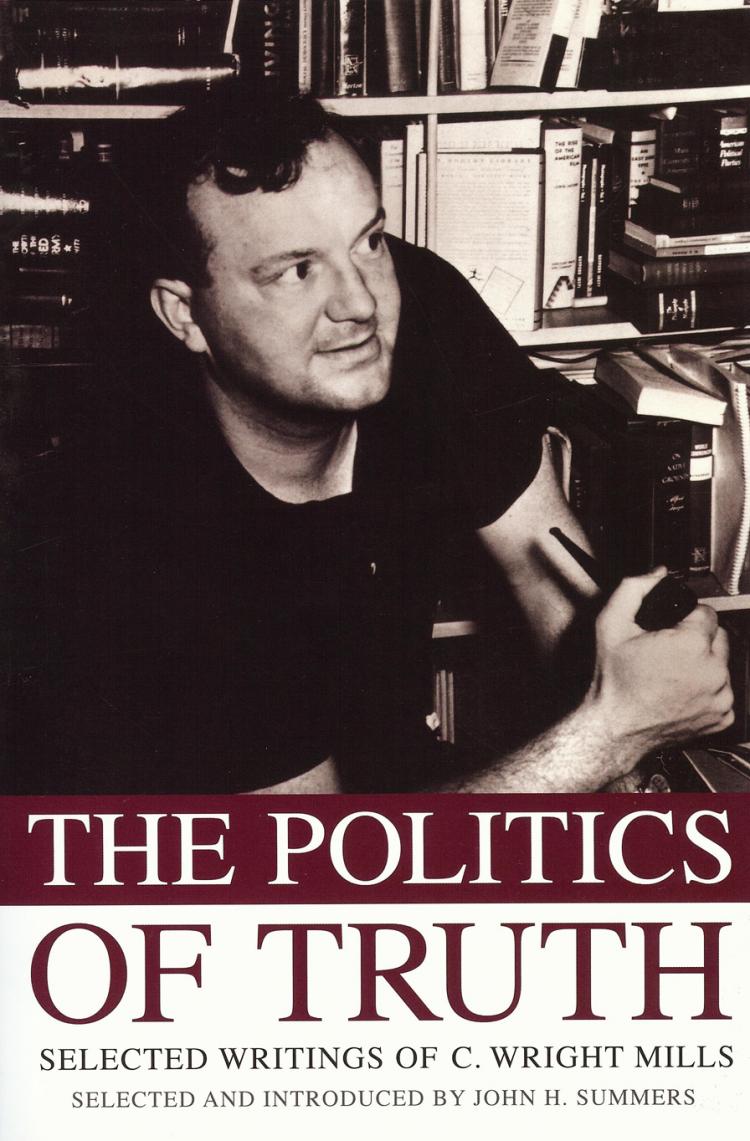

Book Review: ‘The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings of C. Wright Mills’

The most influential sociologist of the post-World War II era, C. Wright Mills took a hard look at modern life.

Front cover of The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings of C. Wright Mills, published by Oxford University Press, Inc. in 2008. Du Won Kang/The Epoch Times

|Updated: