“Nothing through passion and ill temper.”

On April 19, 1861, Private Luther Ladd became the first casualty of the Civil War. A seventeen–year–old mechanic from Massachusetts, Ladd had enlisted in the army with a sense of adventure and pro-Union patriotism. He was killed less than four days into his first mission when the citizens of Baltimore rioted as the 6th Massachusetts Infantry tried to make its way through the city to Camden train station. Within the next four years, over half a million enlisted soldiers would die; while thousands more Americans would become non-enlisted casualties of starvation, disease, suicide, and race-related violence.

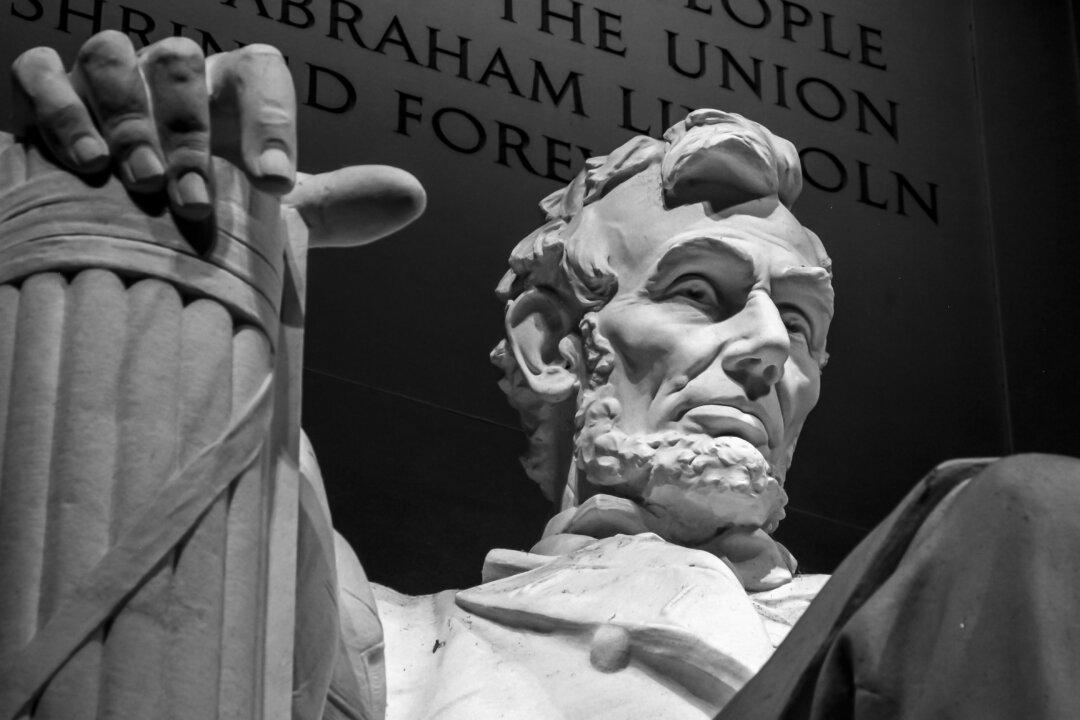

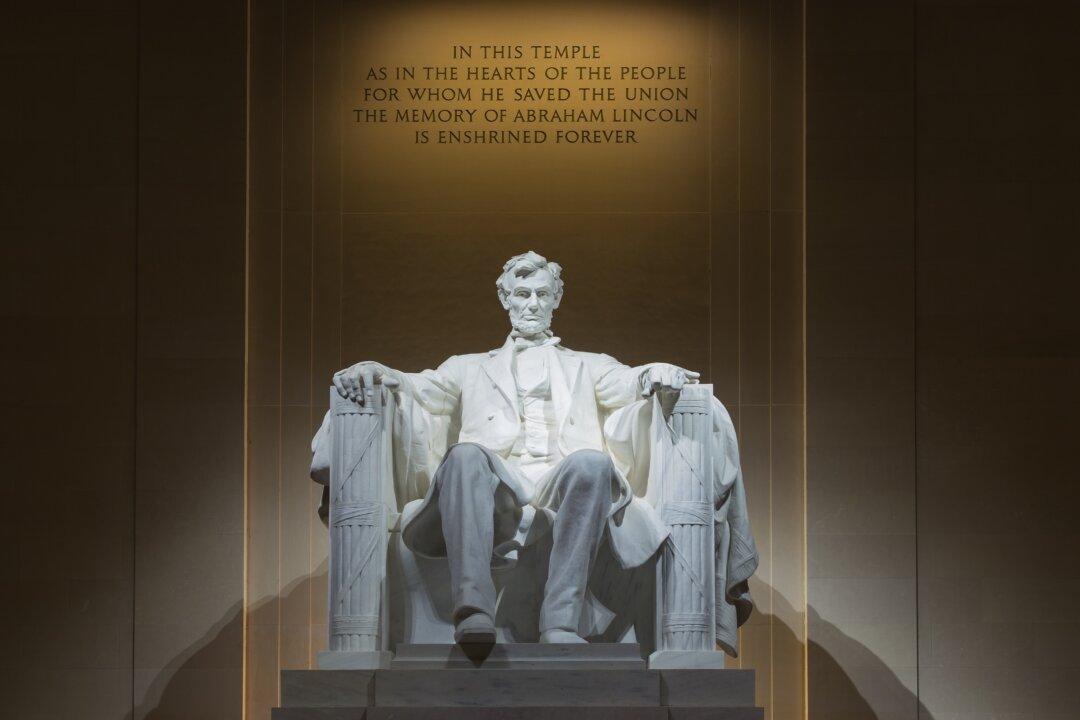

In terms of lives lost, the Civil War remains the costliest military conflict in American history. Cities were burned, entire landscapes ransacked, and throughout it all there is ample evidence to suggest that Abraham Lincoln grieved deeply at the violence and bloodshed washing over the nation.

Numerous anecdotes exist about Lincoln’s struggle to find peace in a nation at war. He was known for personally interceding when distraught widows wrote to him begging for a son to be discharged so the veteran could help support his siblings at home, or for a soldier’s salary to be released when it was being withheld for some minor infraction. Lincoln’s own bouts with “melancholia” are well documented, and his sadness and frustration at the massive loss of life is at the forefront of his writings during his years in the White House.

Yet equally as obvious as Lincoln’s pain is his determination to rebuild and create a stronger nation. Throughout Lincoln’s legal and political career he sought to find resolution—to create compromises that would allow opposing forces to each bend, but not break. In hindsight this characteristic lends itself to both criticism and praise. But as a leader in a time of crisis, Abraham Lincoln drew strength as a man of a select few absolutes. In those principles that he held sacred, Lincoln was as unyielding as granite; he was willing to pursue every means necessary to save the Union. At the same time, he was a leader who chose to look beyond his own ambition to envision a nation where Americans would have to live together after this great conflict had finally ended. He tempered determination with compassion, and endurance with flexibility. Though he would never live to see the Union he fought so valiantly for, Lincoln’s steady guidance provided a framework for Americans to build peace upon long after his death.

Passionately Pursue Peace

It is always magnanimous to recant whatever we may have said in passion.

—Letter to William Butler; February 1, 1839

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

—Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address; March 4, 1861

Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can ... As a peacemaker the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man.

—Fragment; written circa July 1850

Can we not come together, for the future? Let everyone who really believes, and is resolved, that free society is not, and shall not be, a failure, and who can conscientiously declare that in the past contest he has done only what he thought best —let everyone have charity to believe that every other one can say as much. Thus let bygones be bygones. Let past differences, as nothing be; and with steady eye on the real issue, let us reinaugurate the good old “central ideas” of the Republic.

—Speech at the Republican banquet in Chicago; December 10, 1856

Let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the other man, this race and that race and the other race being inferior and therefore they must be placed in an inferior position. Let us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout this land, until we shall once more stand up declaring that all men are created equal.

—Reply to Stephen Douglas; July 10, 1858