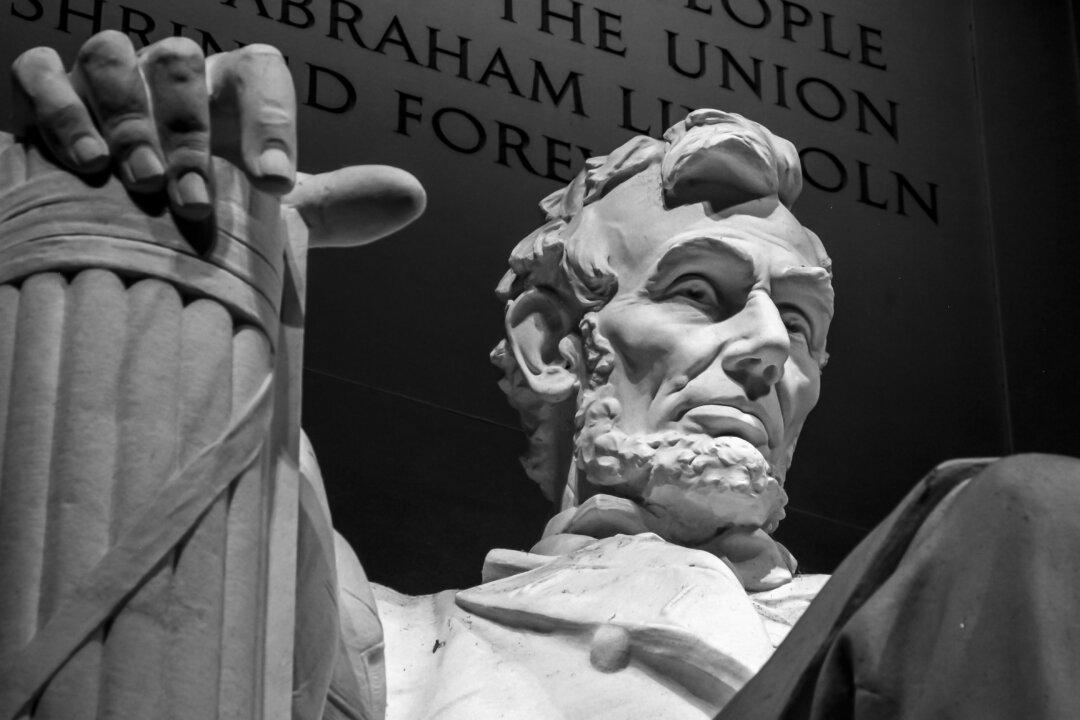

Victory without Vengeance

I shall do nothing in malice. What I deal with is too vast for malicious dealing.

—Letter to Cuthbert Bullitt; July 28, 1862

Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully.

—Lincoln’s second Inaugural Address; March 4, 1865

There is no grievance that is a fit object of redress by mob law.

—Speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum; January 27, 1838

While we must, by all available means, prevent the overthrow of the government, we should avoid planting and cultivating too many thorns in the bosom of society.

—Letter to Edwin M. Stanton; March 18, 1864

Let us at all times remember that all American citizens are brothers of a common country, and should dwell together in the bonds of fraternal feeling.

—Speech at Springfield, Illinois; November 20, 1860

When men take it in their heads today, to hang gamblers, or burn murderers, they should recollect, that, in the confusion usually attending such transactions, they will be as likely to hang or burn some one, who is neither a gambler nor a murderer as one who is; and that, acting upon the example they set, the mob of tomorrow, may, and probably will, hang or burn some of them, by the very same mistake.

—Speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum; January 27, 1838

But the election, along with its incidental, and undesirable strife, has done good too. It has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great civil war. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility. It shows also how sound, and how strong we still are. It shows that, even among candidates of the same party, he who is most devoted to the Union, and most opposed to treason, can receive most of the people’s votes. It shows also, to the extent yet known, that we have more men now, than we had when the war began.

—Reply to a spontaneous serenade; November 10, 1864

It is exceedingly desirable that all parts of this great confederacy shall be at peace, and in harmony, one with another. Let us Republicans do our part to have it so. Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper. Even though the Southern people will not so much as listen to us, let us calmly consider their demands, and yield to them if, in our deliberate view of our duty, we possibly can.

—Address at Cooper Institute; February 27, 1860 The severest justice may not always be the best policy.

—Veto message; July 17, 1862

I have not heard near so much upon that subject as you probably suppose; and I am slow to listen to criminations among friends, and never expose their quarrels on either side. My sincere wish is that both sides will allow bygones to be bygones, and look to the present and future only.

—Letter to unknown; August 31, 1860

Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong, as silly and as wise, as bad and as good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.

—Reply to a spontaneous serenade; November 10, 1864

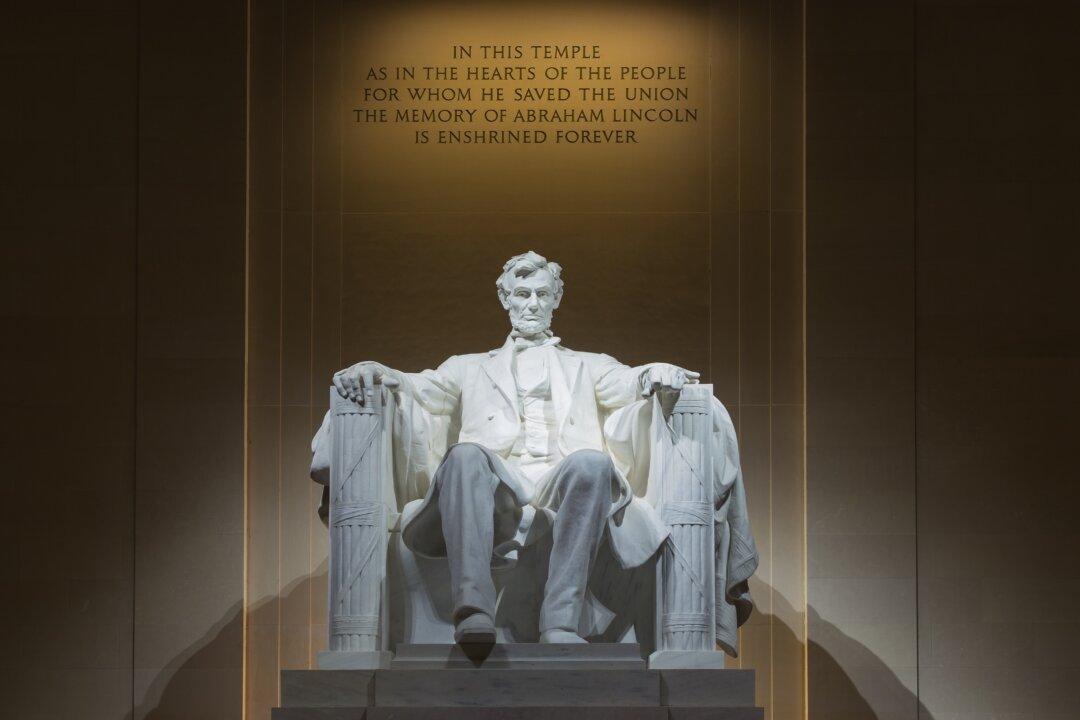

To Build a New Future without Forgetting the Past

I distrust the wisdom if not the sincerity of friends who would hold my hands while my enemies stab me.

—Letter to Reverdy Johnson; July 26, 1862

And then there will be some black men who can remember that with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation, while I fear there will be some white ones unable to forget that with malignant heart and deceitful speech they strove to hinder it.

—Letter to James C. Conkling; August 26, 1863

If we reject and spurn them, we do our utmost to disorganize and disperse them. We, in effect, say to the white man: You are worthless or worse; we will neither help you, nor be helped by you. To the blacks, we say: This cup of liberty, which these, your old masters, hold to your lips, we will dash from you, and leave you to the chances of gathering the spilled and scattered contents in some vague and undefined when, where, and how. If this course, discouraging and paralyzing both white and black, has any tendency to bring Louisiana into proper, practical relations with the Union, I have so far been unable to perceive it. If, on the contrary, we recognize and sustain the new government ... the converse of all this is made true. We encourage the hearts and nerve the arms of twelve thousand to adhere to their work, and argue for it, and proselyte for it, and fight for it, and feed it, and grow it, and ripen it to a complete success. The colored man, too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy, and daring to the same end.

—Lincoln’s last public address; April 11, 1865

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to “preserve, protect, and defend it.”

—Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address; March 4, 1861

Our Republican robe is soiled and trailed in the dust. Let us purify it. Let us turn and wash it white in the spirit if not the blood of the Revolution. Let us turn slavery from its claims of moral right, back upon its existing legal rights and its arguments of necessity. Let us return it to the position our fathers gave it, and there let it rest in peace. Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it the practices and policy which harmonize with it. Let North and South, let all Americans, let all lovers of liberty everywhere, join in the great and good work. If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union, but we shall have so saved it as to make and to keep it forever worthy of the saving.

—Reply to Stephen Douglas; October 16, 1854

On principle I dislike an oath which requires a man to swear he has not done wrong. It rejects the Christian principle of forgiveness on terms of repentance. I think it is enough if the man does no wrong hereafter.

—Note to the Secretary of War; February 5, 1864