By Stephanie Breijo

From Los Angeles Times

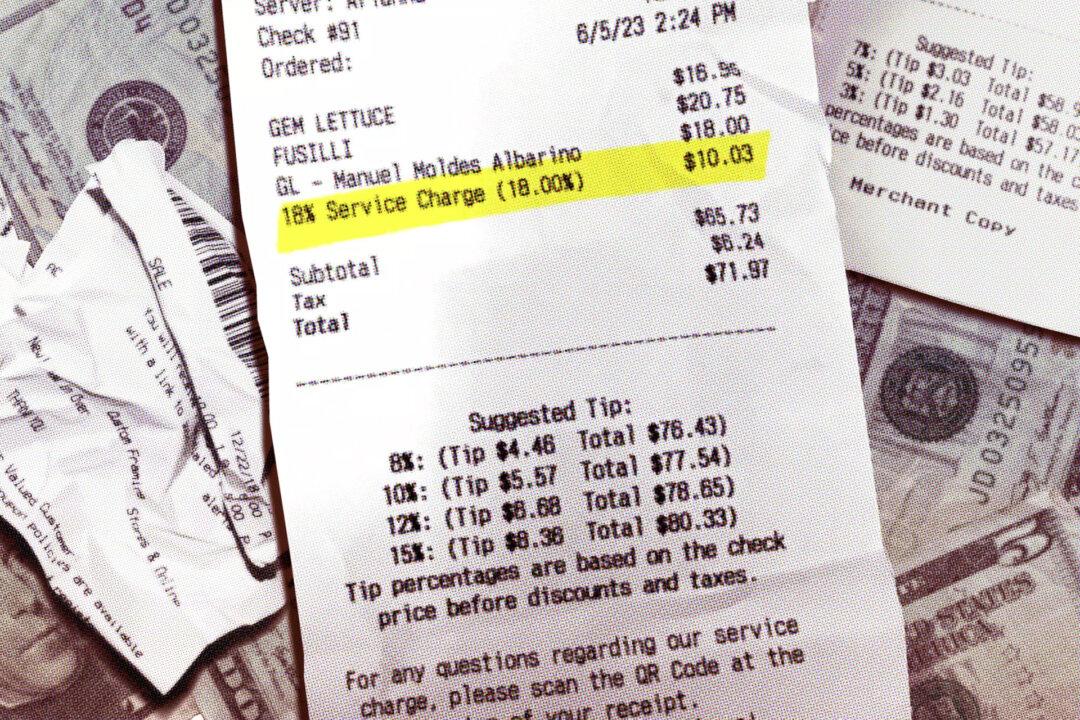

Coming this summer is a new state law that bans unadvertised service fees, surcharges and other additional costs that are added to the end of a bill for meals or delivery service.

Coming this summer is a new state law that bans unadvertised service fees, surcharges and other additional costs that are added to the end of a bill for meals or delivery service.