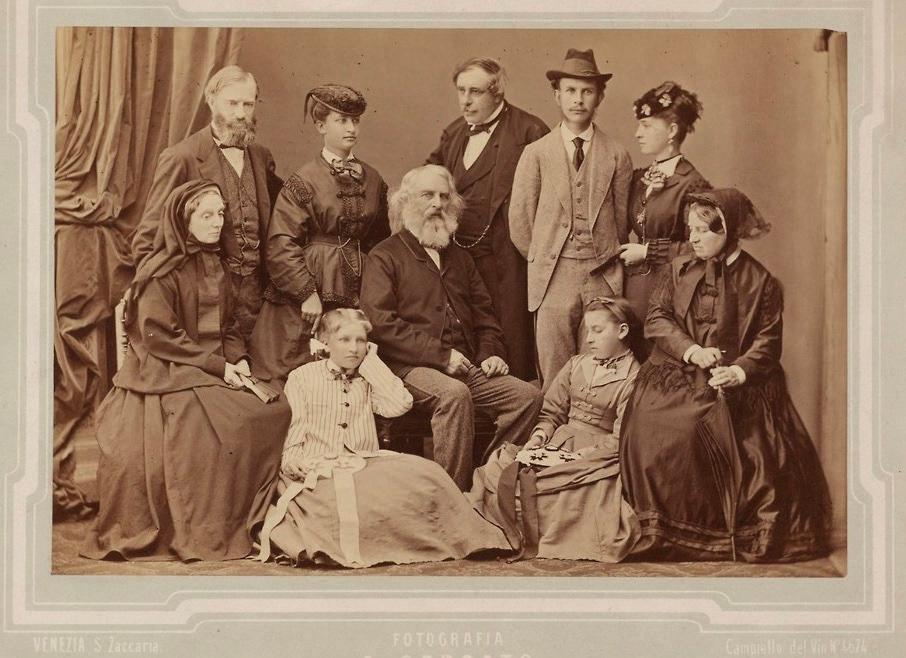

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s popularity among average Americans of his day is something contemporary poets dream about. An international celebrity, he dispensed pre-signed autographs to the many fans who visited his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, hoping to meet the author of “Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Song of Hiawatha.” His work is famous for his placid optimism, and critics today often deride it as shallow. But beneath the surface of the galloping meters and charming imagery lies an undercurrent of melancholy—even of profundity. His love life served as an inspiration to his verse, and when his two marriages ended in tragedy, he coped with despair by creating some of the most life-affirming poetry ever written.

First Love

In 1831, Longfellow, age 24, married Mary Potter, the beautiful and well-educated daughter of a Boston judge. He was drawn to her “pure heart and guileless disposition,” and Mary, too, was smitten. Longfellow was aspiring toward his boyhood dream of becoming a professional writer but struggled to find his literary voice. It was Mary who influenced his decision to resume writing poetry, a youthful practice that had fallen into neglect since he became a professor at Bowdoin College.

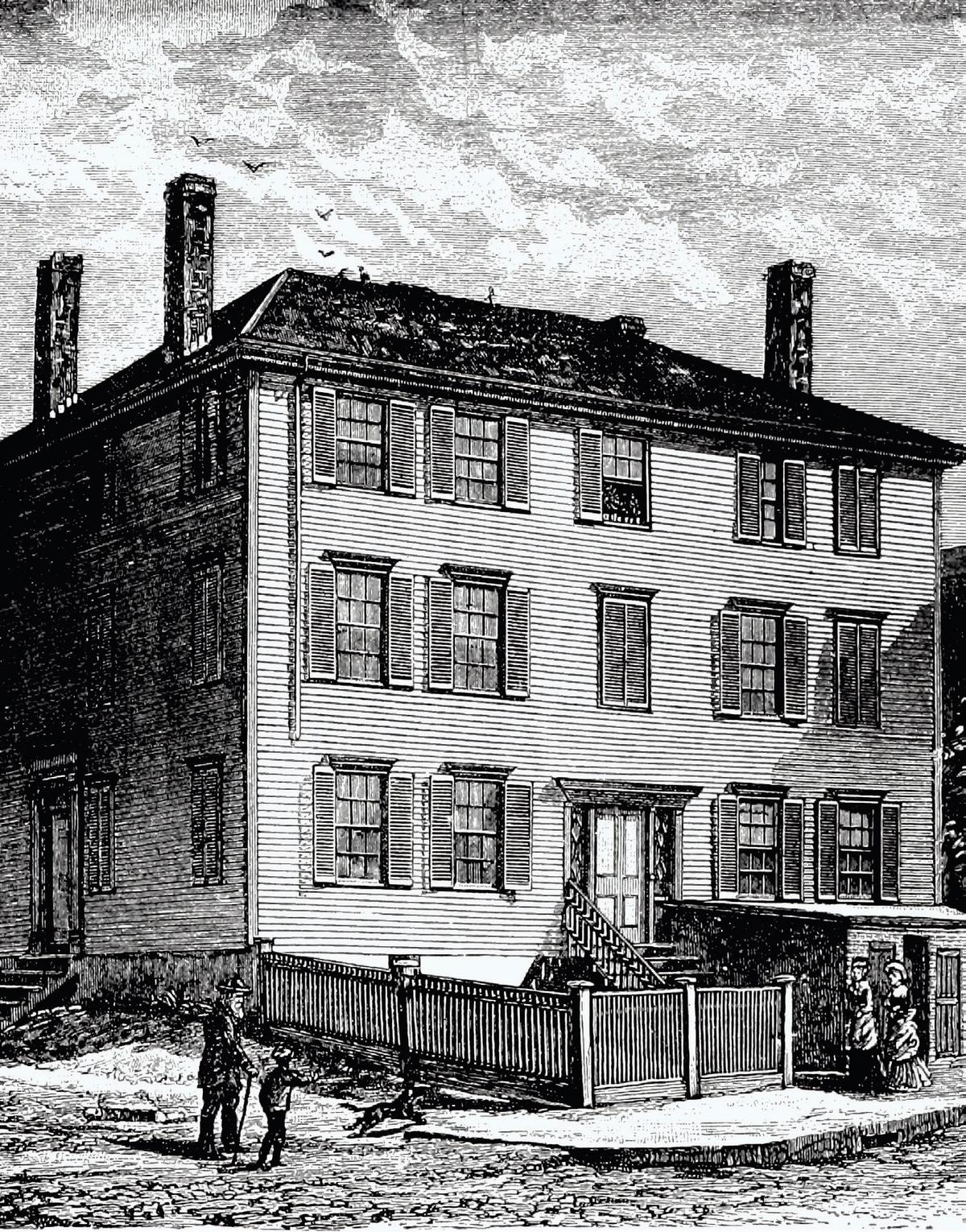

Longfellow’s birthplace, located on the corner of Hancock and Fore streets in Portland, Maine, was demolished in 1955. Public domain