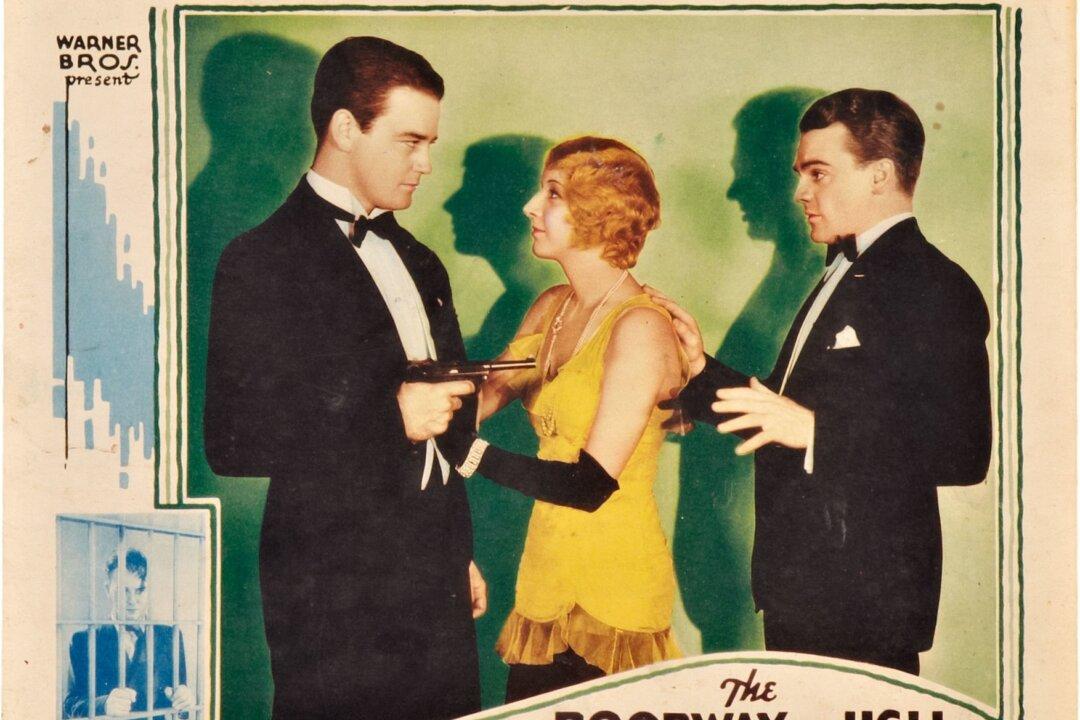

Would you feel sympathy for a cold-blooded murderer? Certain types of crime seem more glamorous than others. Gangsters from the 1920s and ‘30s, particularly in Chicago, were celebrities in their own day, and they remain icons of the Prohibition era. Hollywood capitalized on the notoriety of gangsters by making them leading men in films and portraying them with popular stars. The Warner Bros. studio was most associated with this genre, making most of the major gangster films in the 1930s.

The gangster genre began shortly after the movies learned to talk, around 1930. It flourished during the early part of the decade at the height of the Great Depression, a chapter of Hollywood history that is now called the Pre-Code Era.