“Four score and seven years ago ...” Even if you can’t tell me where these six words come from, there is a good chance that you recognize them. But why? They do not offer wisdom or a witty saying; they are just numbers.

In fact, you remember this phrase because of the music behind the words. The phrase falls into a simple rhythm, the iambic, which is often mimicked in poetry.

If you don’t recall from your high school English class, an iamb is a pair of syllables, or sound units, with the first syllable being unstressed and the second stressed.

In the opening words to President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, there are four iambs (stressed syllables in caps): 1. four SCORE; 2. and SEV; 3. en YEARS; 4. aGO. It is subtle, but the persistence of these rather meaningless six words in my brain and yours seems like compelling evidence of the power of musical language.

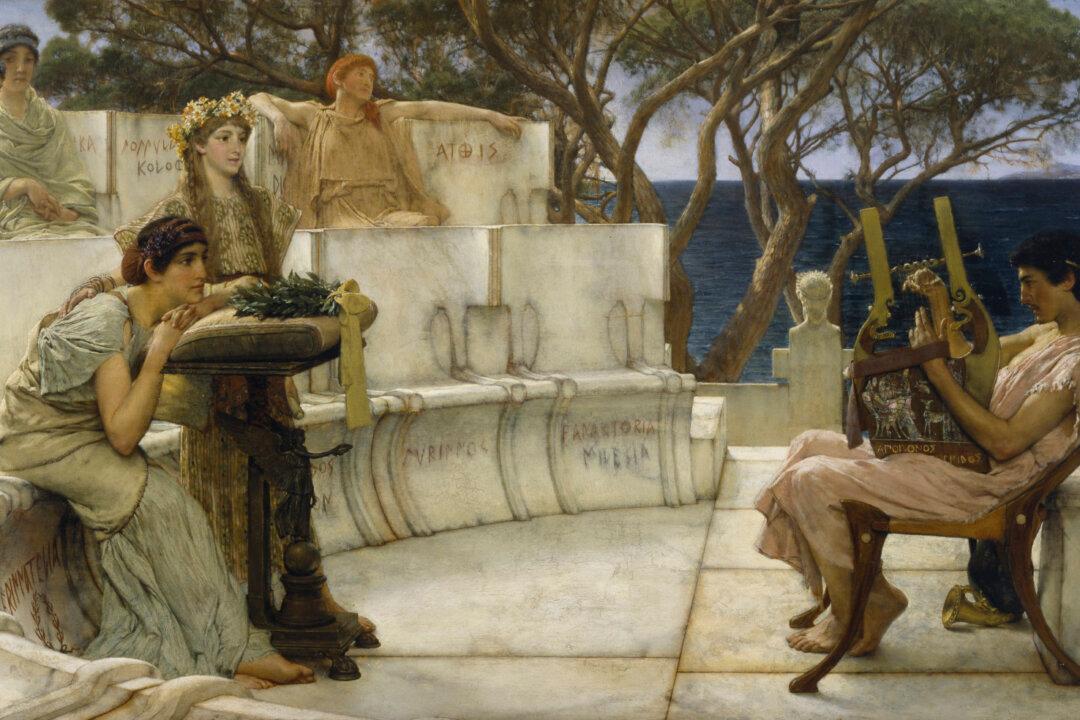

Here we'll look at some classical poems that draw on this enchanting musical power to render beauty in ways that are not only enjoyable but also inspiring. They may even help you write your next greeting card message or Facebook post. The selected poems are written about music, but musical-sounding words theoretically can be used on any topic. Even death and war, as Lincoln showed.

These poems must be read aloud for you to hear the music. Preferably to a room of rapt spectators, but by yourself is fine, too.

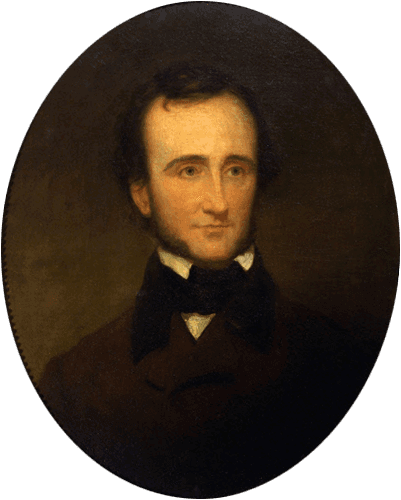

We begin with an excerpt of an exceptionally musical poem by the great Romantic American poet Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849). Here, Poe uses the reverse of an iamb, called the trochee, with the first syllable being stressed and the second unstressed. He uses brilliant repetition, rhyme, alliteration, and other techniques to create a poem that seems to dance off the page.

Next is a poem by living poet J. Don Shook, a writer, actor, director, and producer who formerly worked for NBC in New York. His poem brings to life Beethoven’s final and greatest symphony, written after the legendary composer had already gone deaf.

Finally, we have a sonnet from living poet C.B. Anderson, who was the longtime gardener for the PBS television series “The Victory Garden.” If you listen closely, you'll hear in each line a steady and exquisite rhythm of two soft beats followed by one hard beat, called an anapest. Here is the first line with the hard syllables capitalized: “just as WHITE as a BLANket of NEW-fallen SNOW.”