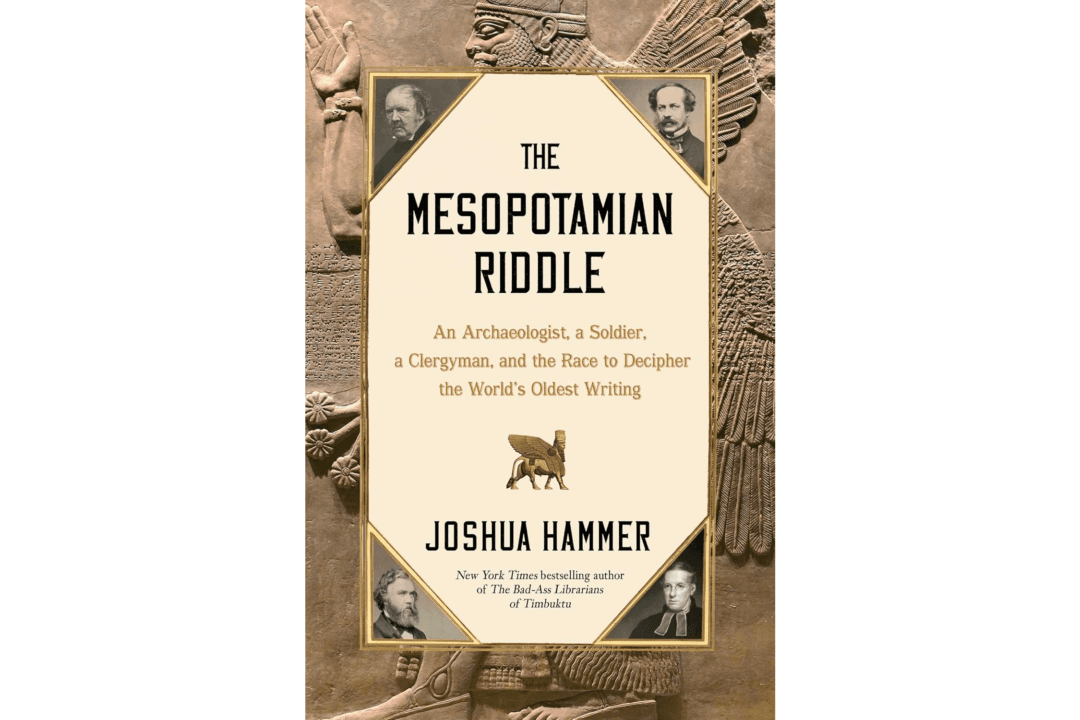

In 1857, three men, alongside many others, accepted an odd challenge: to independently translate 800 lines of Akkadian text. They were not to communicate with each other or to publish results until all finished. The sealed translations would be sent to the Royal Asiatic Society in Mayfair, an area in London. There, six judges, distinguished linguists, would examine the results.

The contest would settle one of the hottest scientific controversies of the mid-19th century. Explorers had been unearthing clay tablets and stone inscriptions covered with wedge-shaped carvings for decades. Some, including the three contestants, insisted the wedges were an ancient form of writing of an extinct language. Others insisted this was nonsense. Critics believed archaeologists and linguists translating the symbols were assigning them arbitrary values.