“Stone walls do not a prison make / Nor iron bars a cage.” These famous words from 17th-century poet Richard Lovelace thrill us like a surge of adrenaline, reminding us that a truly free human soul can break all fetters.

Neither war, prison, nor the loss of his beloved could suppress the exultant spirit of Richard Lovelace. His gallantry and undying love of king, country, and duty shine through his poems like a blaze of sunlight upon an uplifted sword, especially in one poem called “To Althea, From Prison,” which Lovelace did, in fact, write while he was imprisoned in the Gatehouse in London. This physical constraint did not restrain his unbounded soul, and the notion of spiritual freedom juxtaposed with physical restriction becomes a major theme of the poem.

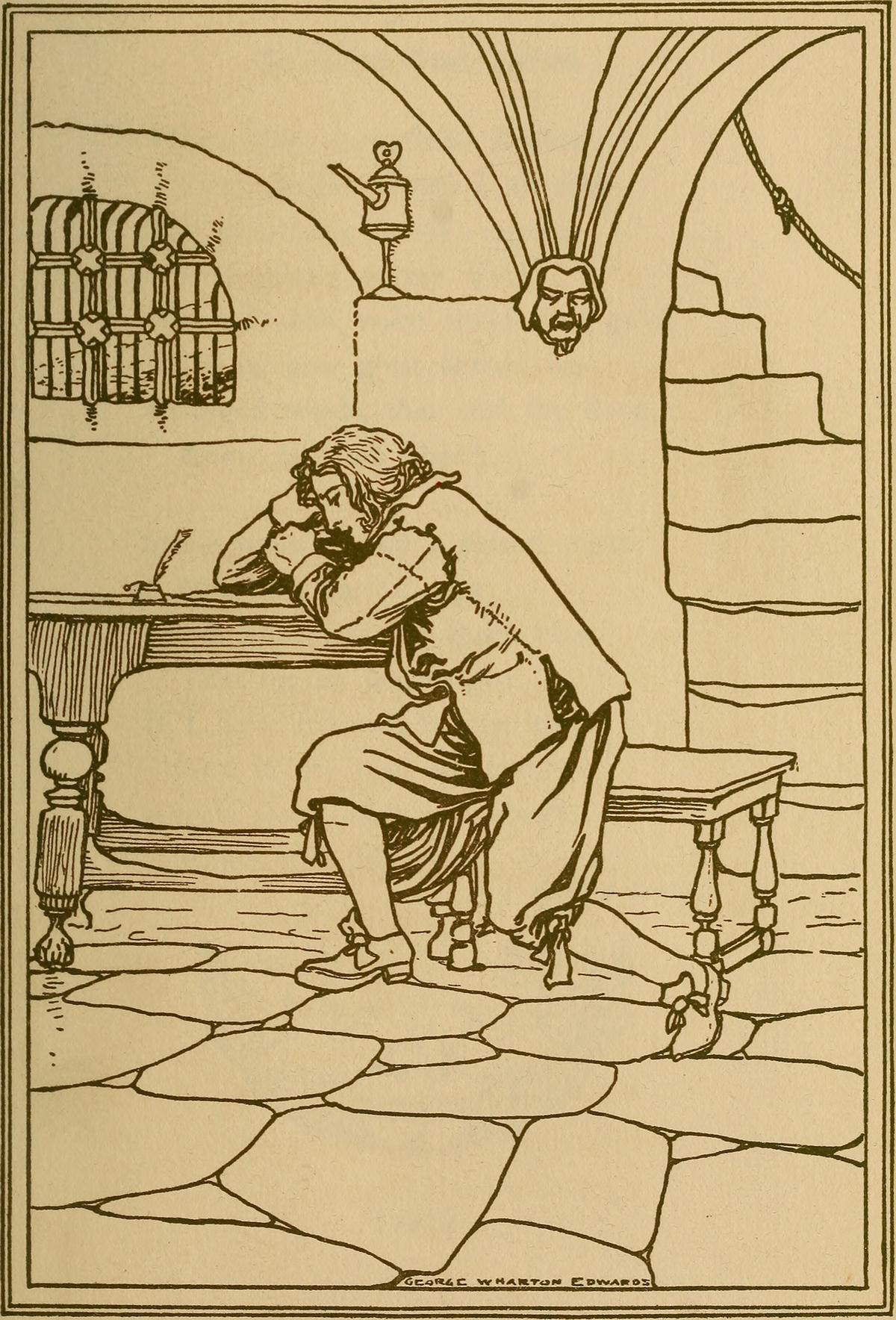

An illustrated plate of Richard Lovelace writing “To Althea From Prison” from “A Book of Old English Love Songs,” 1897, by Hamilton Wright Mabie with illustrations by George Wharton Edwards. Internet Archive. Public Domain