In the fall of 2014, Sarah Ogilvie spent a few days bidding farewell to Oxford University before setting off for a new job in the United States. Near the end of that nostalgic goodbye, she revisited the basement of the Oxford University Press and, in particular, an obscure corner where the archives of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) are stored. Among her other professional positions, she had worked as an editor for the OED and had many fond memories of the days she’d spent in the building.

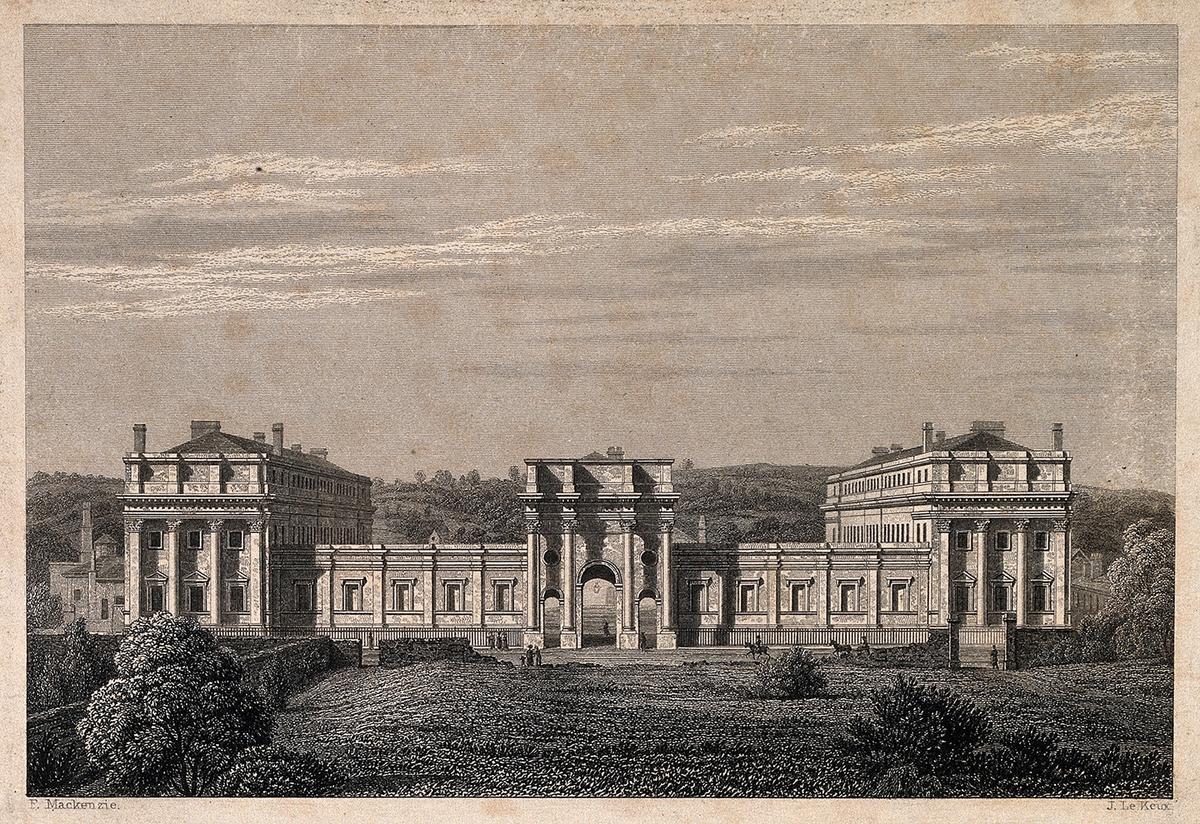

A line engraving of the Oxford University printing house, 1833, by J. Le Keux after F. Mackenzie. Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0 DEED