NEW YORK—It came and went like a shooting star. “The Art of Watches Grand Exhibition” in New York seemed to leave everyone who entered its doors simply awestruck. This event happens only once every 11 years or so, when the exclusive, family-owned Swiss watchmaking company Patek Philippe decides to share its heritage with the public on a grand scale.

Admission to the two-storied pop-up museum built inside Cipriani—the lavish Italian Renaissance-inspired venue on 42nd Street—was free and open to the public. It welcomed more than 2,400 people a day, like clockwork. The buzz over the exhibition peaked on the closing day of July 23, when people stood in a line that extended around the block to 41st Street.

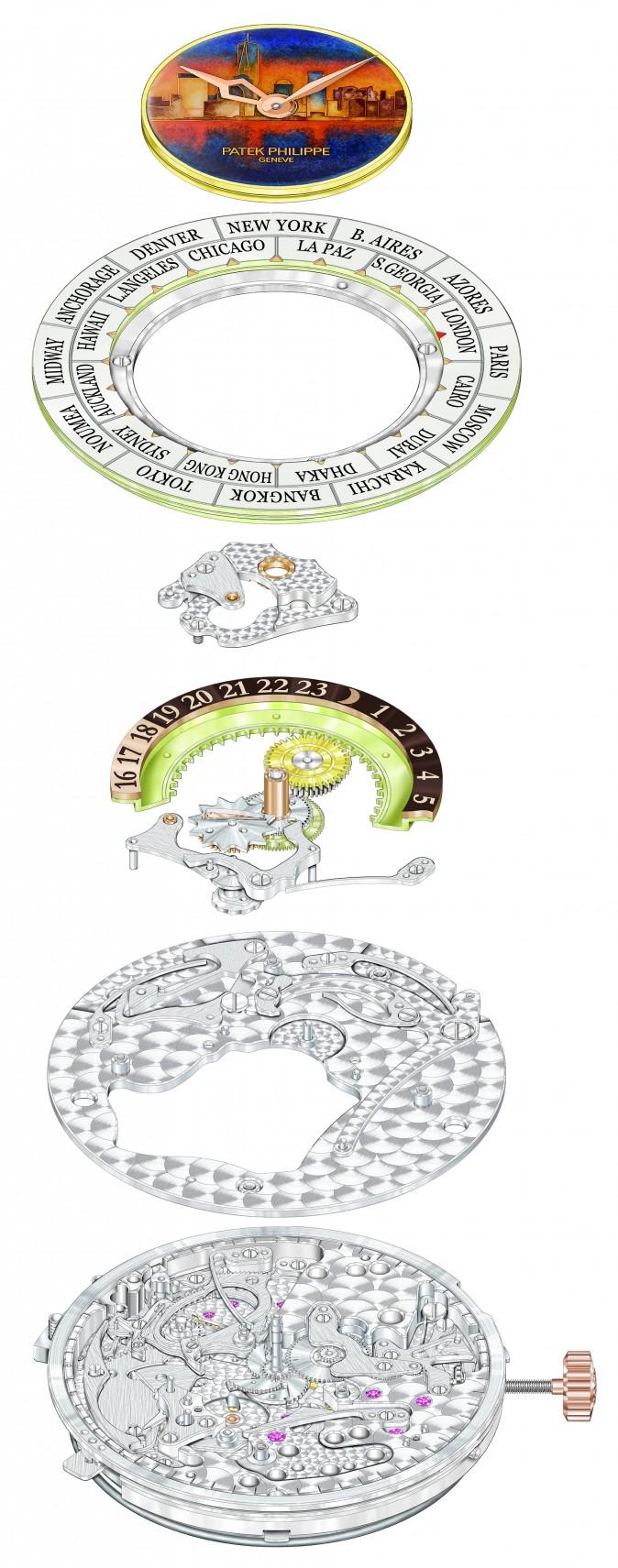

But how could an exhibition of a Swiss watch company be any different from going into a retail watch store, you might ask? “The Art of Watches” was geared to take visitors on a journey of discovery. It unraveled the mysteries of some of the most complicated timepieces ever made. Ultimately, it answered the question, what is a mechanical timepiece, really?

Ten Rooms of Wonderment

The exhibition progressed in levels of complexity. It started with a short film explaining how the company started, then eased you into a room showcasing their current collection. Down the hall and into a replica of the Napoleon Room from the Patek Philippe Salons in Geneva, you could see special New York editions, signaling the company’s strong ties with the U.S. market.

In the next room, you dove into historic pieces from the collections of the Patek Philippe Museum, including, for instance, the first wristwatch, a pocket watch owned by Queen Victoria, and a pair of dual perfume pistols with watches, among other fascinating pieces. Next to it, the U.S. Historic Room displayed notable timepieces, such as the desk clock gifted to John F. Kennedy a day after his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in 1963, as well as watches owned by General Patton; jazz giant Duke Ellington; baseball legend Joe DiMaggio; the trainer of the famous racehorse Seabiscuit, Tom Smith; and the rival collectors and industry titans Henry Graves Jr. and James Ward Packard. Further along, people lingered in the Rare Handcrafts Gallery, where artisans demonstrated miniature marquetry-making, enameling, engraving, and jewel setting.

[gallery size=“medium” ids=“2275252,2274794,2275177,2275175,2275179,2275188,2275230,2274796,2274809,2274802,2274840,2274843,2274846,2275337,2275200,2275258”]

Upstairs, you could talk with watchmakers who answered questions by actually showing you various mechanisms, including the inner workings and charms of a minute repeater. Minute repeaters strike the hours, quarters, and minutes, some on request, by operating a sliding knob. These are the most difficult mechanical timepieces to create, and it takes about 15 years for a watchmaker to learn how to make them.