On Christmas break during my last year of law school in 1970, I felt pretty good, with one semester to go before I might take on the world and become a practicing attorney.

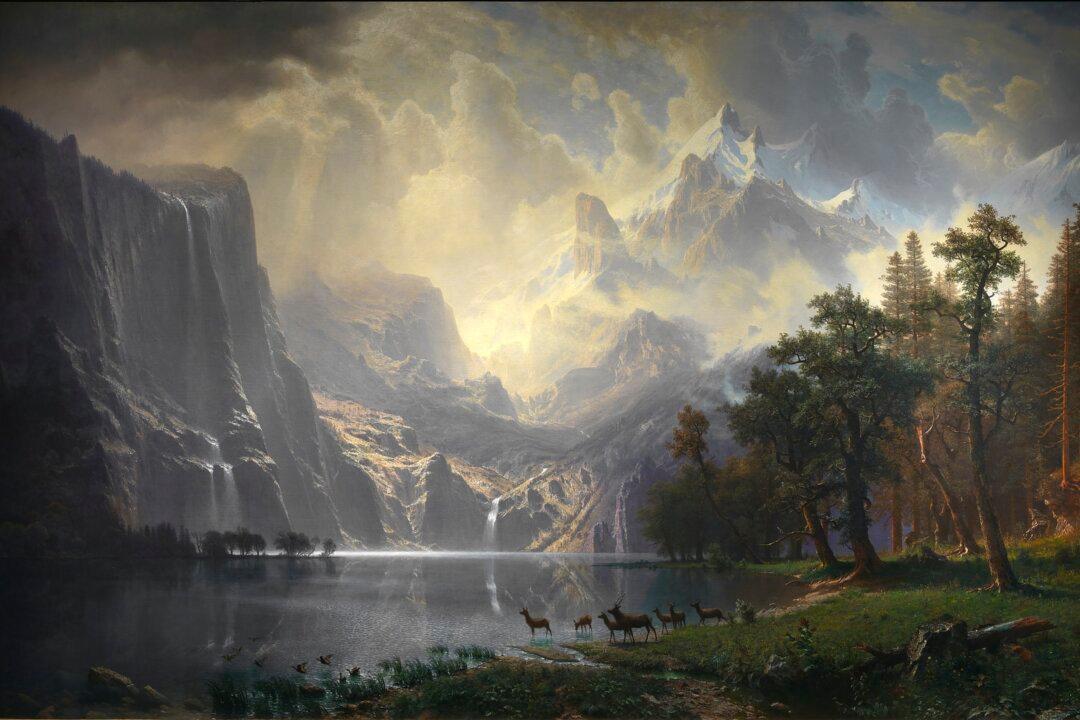

I borrowed my mother’s old gray Rambler and drove to the nearby Cherry Hill Mall in South Jersey for some last-minute shopping. I chanced to walk into an art gallery, wondering what mall art might look like. High up on a wall was a painting that took my breath away.