Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore, So do our minutes hasten to their end; Each changing place with that which goes before, In sequent toil all forwards do contend. Nativity, once in the main of light, Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown‘d, Crooked eclipses ’gainst his glory fight, And Time that gave doth now his gift confound. Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth And delves the parallels in beauty’s brow, Feeds on the rarities of nature’s truth, And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow: And yet to times in hope, my verse shall stand Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

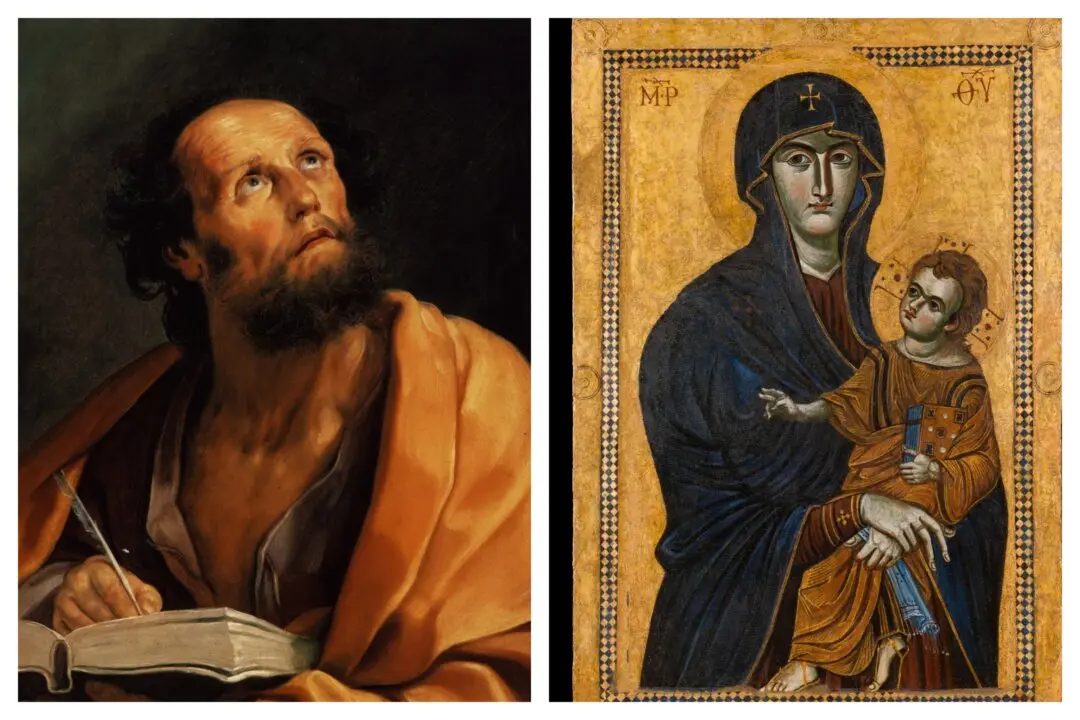

It often seems as though the sea inspires two sensations in most everyone who beholds it. One is a sense of peace and tranquility before the vast expanse of blue, lulled by the playful lapping of waves upon the shore. The other is a sense of one’s own insignificance and the brevity of our lives in face of the sea’s immensity and untamable power.Born in 1564, William Shakespeare incorporated imagery of the sea many times in his writings. One such example is Sonnet 60. The poem was published in 1609 and is contained in the “Fair Youth” sequence of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets, along with those that address a fair youth with whom the poet shares a deep friendship.