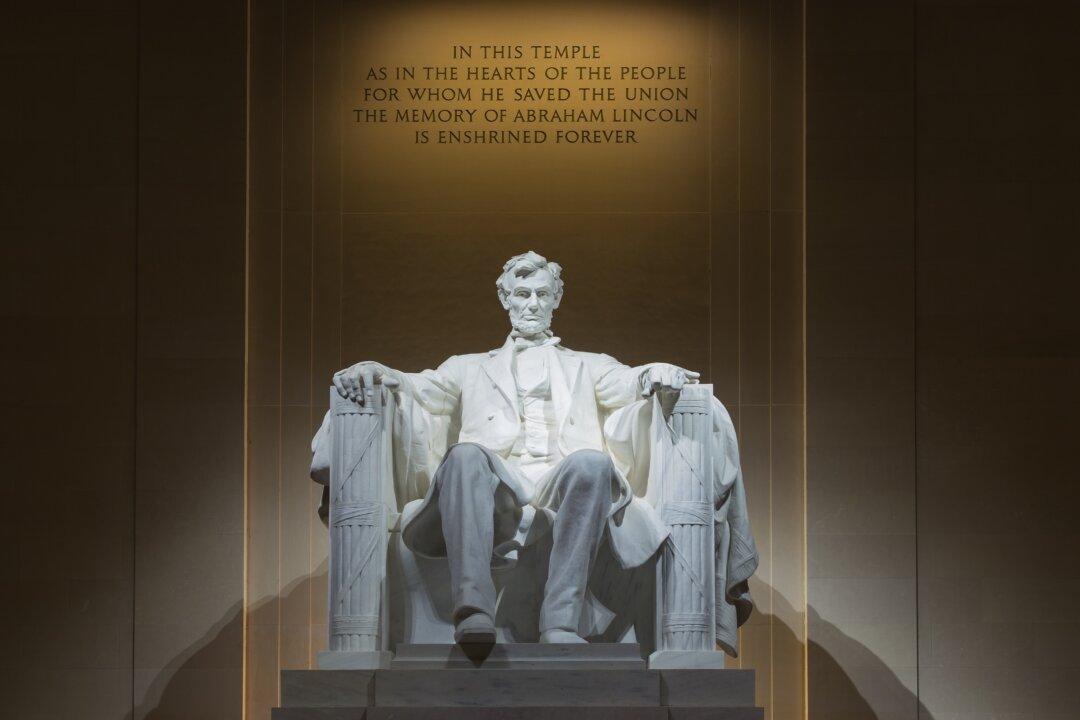

Emotional Control

Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the material for our future support and defense. Let those materials be molded into general intelligence, sound morality and, in particular, a reverence for the Constitution and laws.... Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock of its basis; and as truly as has been said of the only greater institution, “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”

—Speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum; January 27, 1838

I hope it will not be irreverent for me to say, that if it is probable that God would reveal His will to others, on a point [emancipation of the slaves] so connected with my duty, it might be supposed that He would reveal it directly to me; for, unless I am more deceived in myself than I often am, it is my earnest desire to know the will of Providence in this matter. And if I can learn what it is, I will do it. These are not, however, the days of miracles, and I suppose it will be granted that I am not to expect a direct revelation. I must study the plain physical facts of the case, ascertain what is possible and learn what appears to be wise and right.

—Reply to the Chicago Committee of United Religious Denominations; September 13, 1862

The true role, in determining to embrace, or reject any thing, is not whether it have any evil in it; but whether it have more of evil, than of good. There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good. Almost everything, especially of governmental policy, is an inseparable compound of the two; so that our best judgment of the preponderance between them is continually demanded.

—Speech in the House of Representatives; June 20, 1848

We do not today know that a colored soldier, or white officer commanding colored soldiers, has been massacred by the rebels when made a prisoner. We fear it, we believe it, I may say,—but we do not know it. To take the life of one of their prisoners on the assumption that they murder ours, when it is short of certainty that they do murder ours, might be too serious, too cruel, a mistake. We are having the Fort Pillow affair thoroughly investigated; and such investigation will probably show conclusively how the truth is.... If there has been the massacre of three hundred there, or even the tenth part of three hundred, it will be conclusively proved; and being so proved, the retribution shall as surely come. It will be matter of grave consideration in what exact course to apply the retribution; but in the supposed case it must come.

—Address to the Sanitary Fair in Baltimore; April 18, 1864

It is my duty to hear all; but, at last, I must, within my sphere, judge what to do, and what to forbear.

—Letter to Charles D. Drake & Others; October 5, 1863

I view this matter [emancipation of the slaves] as a practical war-measure, to be decided on according to the advantages or disadvantages it may offer to the suppression of the rebellion.

—Reply to the Chicago Committee of United Religious Denominations; September 13, 1862

Accountability and Criticism

He who does something at the head of one regiment, will eclipse him who does nothing at the head of a hundred.

—Letter to Maj. Gen. Hunter; December 31, 1861

This government cannot much longer play a game in which it stakes all, and its enemies stake nothing. Those enemies must understand that they cannot experiment for ten years trying to destroy the government, and if they fail still come back into the Union unhurt.

—Letter to August Belmont; July 31, 1862

I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac. Of course I have done this upon what appear to me to be sufficient reasons. And yet I think it best for you to know that there are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and skilful soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix politics with your profession, in which you are right.... But I think that during Gen. Burnside’s command of the army, you have taken counsel of your ambition, and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country, and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer. I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the army and the government needed a dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship. The government will support you to the utmost of its ability, which is neither more nor less than it has done and will do for all commanders. I much fear that the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the army, of criticizing their commander, and withholding confidence from him, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you as far as I can, to put it down. Neither you, nor Napoleon, if he were alive again, could get any good out of an army, while such a spirit prevails in it. And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.

—Letter to Maj. Gen. Hooker; January 26, 1863

It is not my purpose to review our discussions with foreign states, because, whatever might be their wishes or dispositions, the integrity of our country and the stability of our Government mainly depend not upon them, but on the loyalty, virtue, patriotism, and intelligence of the American people.

—Lincoln’s first State of the Union Address; December 3, 1861

I regret to find you denouncing so many persons as liars, scoundrels, fools, thieves, and persecutors of yourself. Your military position looks critical, but did anybody force you into it? Have you been ordered to confront and fight ten thousand men, with three thousand men? The government cannot make men; and it is very easy, when a man has been given the highest commission, for him to turn on those who gave it and vilify them for not giving him a command according to his rank.

—Letter to Maj. Gen. Blunt; August 18, 1863

If, then, I was guilty of such conduct, I should blame no man who should condemn me for it; but I do blame those, whoever they may be who falsely put such a charge in circulation against me.

—Open letter to the Voters of the Seventh Congressional District; July 31, 1846

(To be continued...)