“Until lately the West has regarded it as self-evident that the road to education lay through great books. No man was educated unless he was acquainted with the masterpieces of his tradition. There never was much doubt in anybody’s mind about which the masterpieces were. They were the books that had endured and that the common voice of mankind called the finest creations, in writing, of the Western mind ... these books shed a light on all our basic problems, and ... it is folly to do without any light we can get.”—Robert M. Hutchins, educator

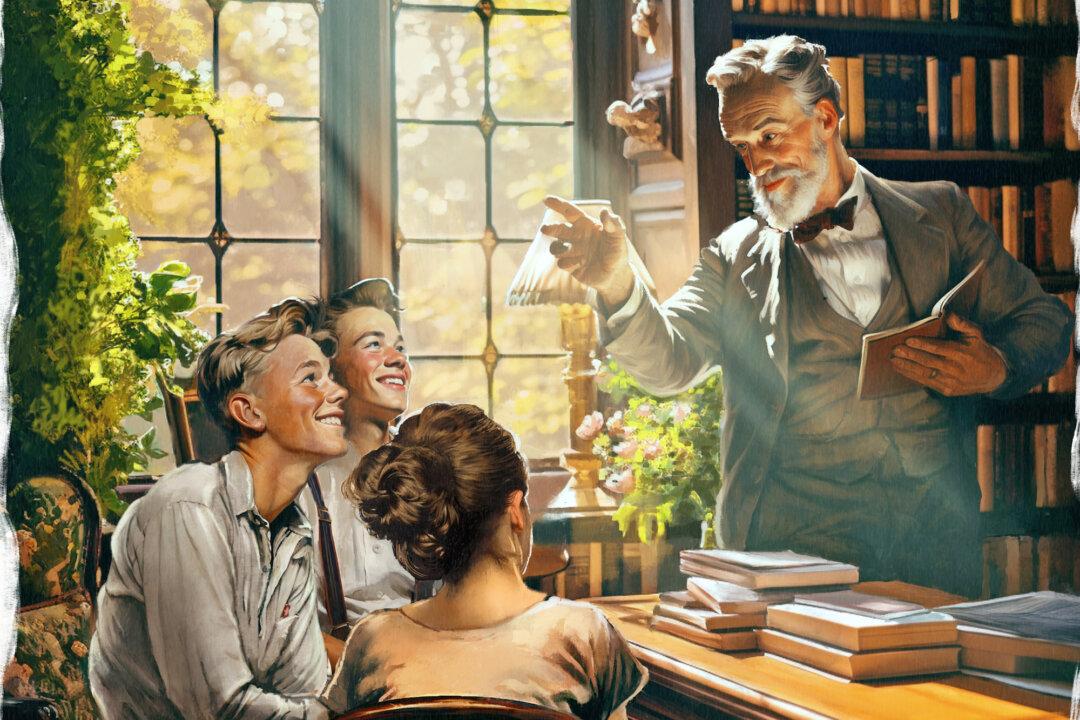

Studying the classics, if done properly, helps us flourish as human beings—it makes us, in a sense, more human as we encounter “the best that has been thought and said,” in Mathew Arnold’s phrase, about the things that matter most: life, death, love, war, justice, beauty, sin, and the like. We learn about the heights to which humanity can rise and the depths to which it can fall. And we enter into the “Great Conversation” about these most fundamental and vital realities, which has been going on for centuries—until just the last few generations, arguably, when we stopped reading the great minds of history, stopped listening to that conversation, and stopped contributing to it.

How can we recover something of this traditional mode of education?