NEW YORK—At the turn of the 20th century, a time when Asian art curators were most interested in Chinese or Japanese art, Stewart Culin dedicated much of his time to Korea. He was an ethnographer, anthropologist, and the Brooklyn Museum’s very first Asian art curator.

Because of his early interest in Korea, the Brooklyn Museum is one of the few American museums to hold a rare collection of Korean art.

“Since our collection of Korean art began early on, we became a place to give Korean art,” said Joan Cummins, Asian art curator at the Brooklyn Museum. “The Met and other museums used to not show interest, so people didn’t give things to the Met; they gave it to us.”

Stewart Culin installed the Korean collection in 1916. The Brooklyn museum is one of the first in the United States to dedicate permanent gallery space for Korean art. The museum has received works from various collectors, some with only one Korean piece.

“So it’s a real mish mash, but it’s a wonderful mish mash,” Cummins said earlier this month during a Korean art connoisseurs’ private viewing of the Brooklyn Museum’s Korean rarities. The event was organized by the Korean Art Society.

Scorched Paintings

At first glance, of the painting “Chrysanthemums, Rock and Bird,” one catches the intricately detailed petals of the chrysanthemum. The exquisite piece is not painted with a brush, but scorched on by various shapes and sizes of metal. The longer the heat is in contact with the paper, the darker a mark it leaves. For a lighter shade, the artist briefly touches the paper with burning metal.

A small group of artisans in the late Joseon Dynasty developed a mastery in manipulating the scorches to create a wide range of tones closely resembling a painted artwork.

“There is a little bit of cheating, a little bit of touching in [with paint] here and there,” Cummins said. “But it is mostly scorch marks, including the calligraphy.”

It’s very unusual for an American museum to hold this collection, Cummins said. It is rare to find such a series of scorched Korean paintings in the United States.

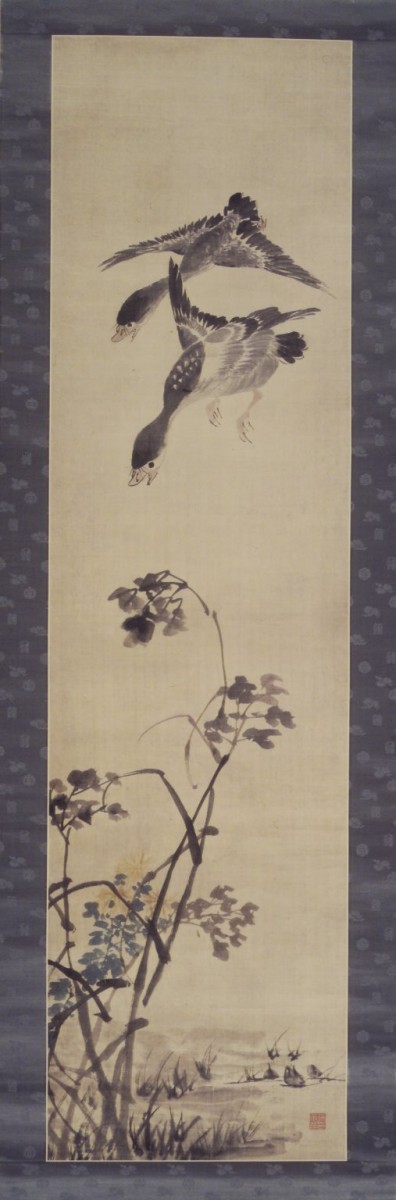

Old Geese

Jang Seung-eop (1843–circa 1897) is the founding father of modern Korean oriental painting and one of Korea’s most celebrated artists. “It’s rare to see his paintings in the U.S.,” said Robert Turley, president of the Korean Art Society.

The painting “Geese and Reeds” is a retirement gift. The title of the painting, pronounced as “noan,” is a play on words in Korean; it translates to “peaceful old age” and “wild geese.”

In a serene waterfront setting decorated with reeds, flowers dance with the wind. One cannot see the artist’s drunken state of mind when viewing the intricate shades of the geese feathers, but the abnormally large and animated heads of the geese might give it away.

Seung-eop grew up as an orphan and taught himself art while he was practically homeless, Turley said. Seung-eop was illiterate in Chinese; thus, his paintings are never signed. “It was unheard of for an artist of his caliber and fame to not be able to read Chinese, but that was how he was—and he was proud of it too.”