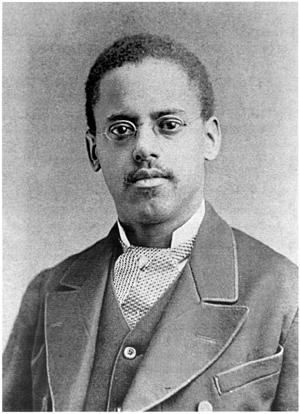

In the late 1830s, George and Rebecca Latimer fled Virginia. The two fugitive slaves worked their way toward Boston around 1842, where they found a home and freedom. This freedom, however, was uncertain due to the fugitive slave laws. When George was arrested and brought to trial as a fugitive, Bostonians defended George’s right to freedom. He received the support of famous abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison and the former slave-turned-orator Frederick Douglass. When an African American preacher paid $400 to the Virginia slavemaster, George was finally free. By then, he and Rebecca were the parents of four children. Their youngest was the bright Lewis Howard Latimer (1848–1928).

Lewis Latimer, a detail-oriented and self-taught inventor, contributed to the development of electric lighting in the 19th century. Public Domain