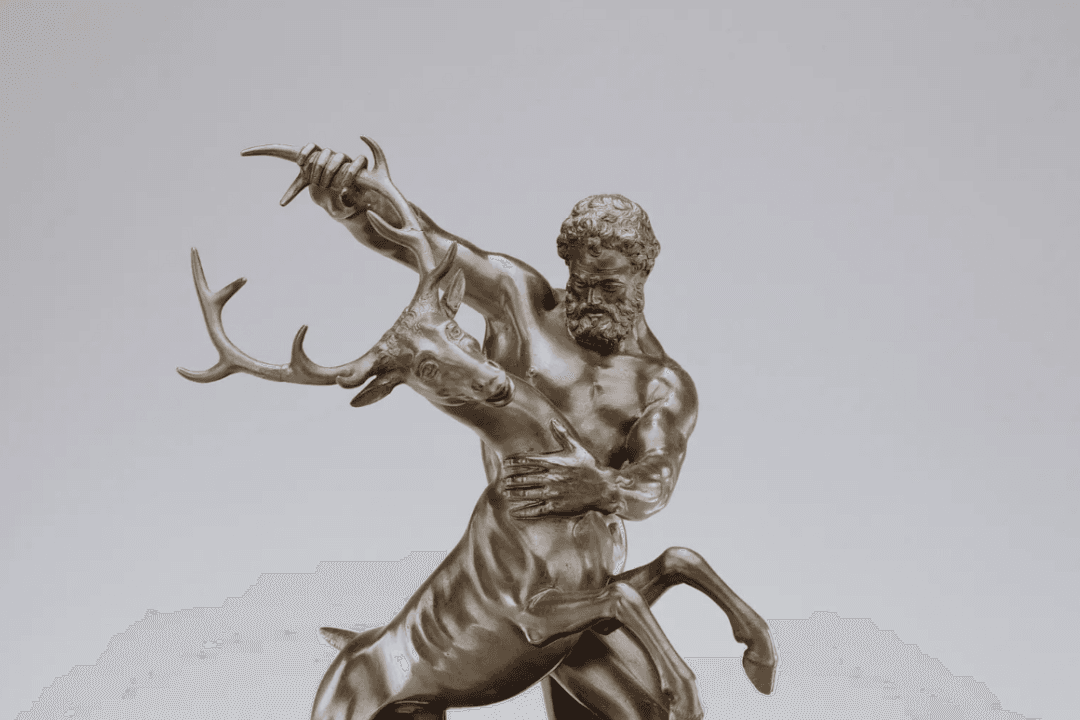

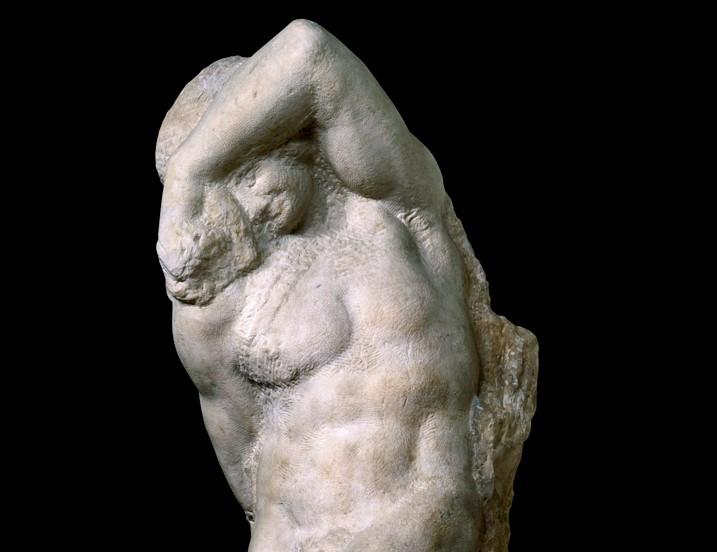

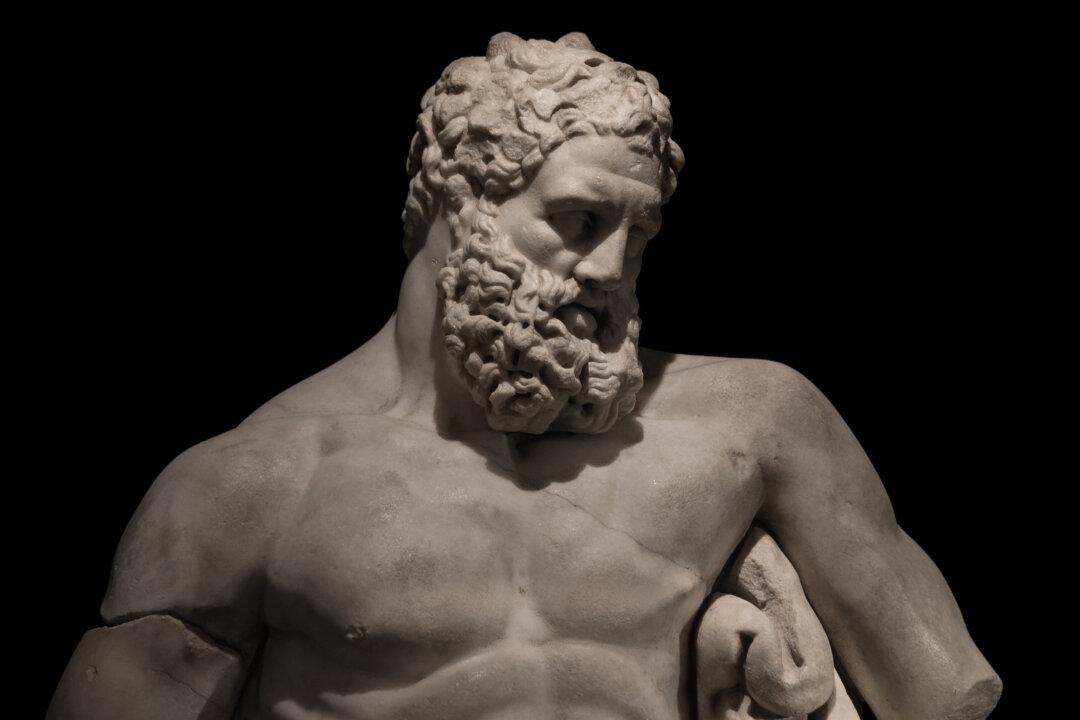

Hercules is one of the most popular characters in Greek mythology. His great strength and courage inspired the Western world. Yet he was a complex figure whose actions did not always make sense. In this series “Our Herculean Tasks,” we will explore Hercules’s 12 labors in search of wisdom for our modern times.

Happy New Year! Many of us are hopeful about this new year and the good things it might bring. Some of us spend the new year thinking about our New Year’s resolutions. We seek to get rid of the bad habits from previous years so that we can live happier and healthier lives.