Sometimes we are blessed with not one, but two mothers whose care and affection shape our lives.

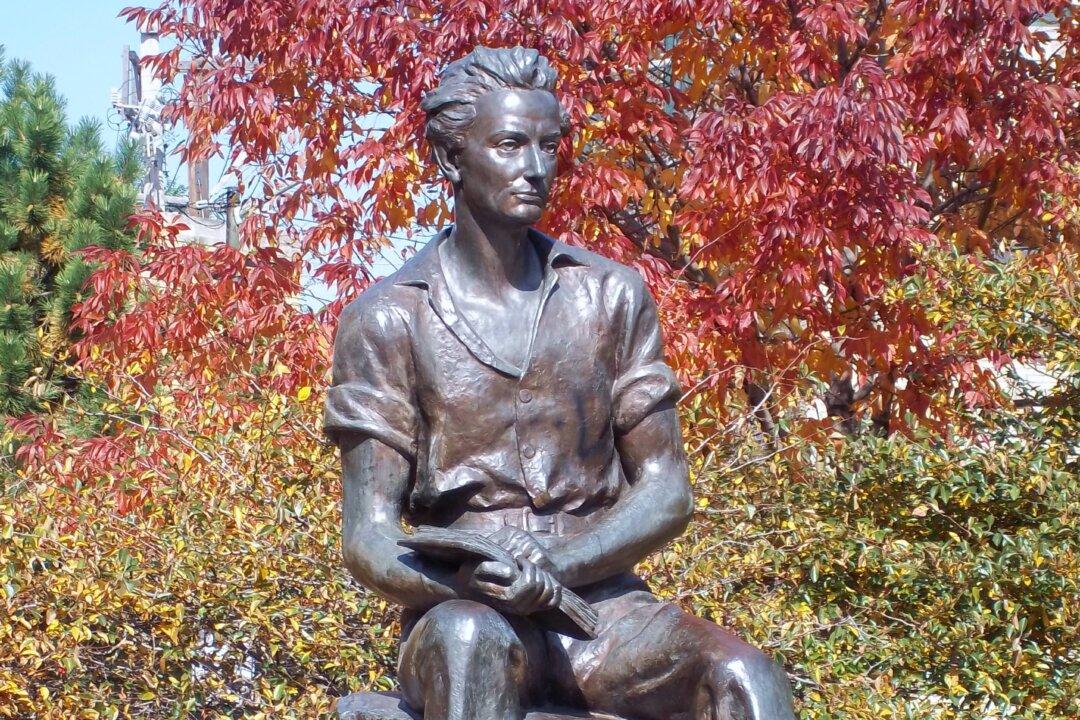

Abraham Lincoln was 9 years old when his mother, born Nancy Hanks, died either of “milk sickness” or consumption. We know little of Nancy other than that she was an intelligent, kind woman who had lost one child in infancy and who loved both her daughter Sarah and young Abraham.