Romania is the land of sights, feelings, and music, and a land rich in culture where Georges Enesco, the great violinist, composer, and conductor is know by all. Here, Enesco is featured on Romanian currency and streets are named after him. He adorns many monuments as well.

Here in a land so rich in tradition, where musicians and artists find and form their own highly individual ways, here wherever I go—into plazas, in hotel lobbies, on the planes—I hear the worst of Western music.

Here, when leaving the hotel, I am escorted by lyrics of someone shooting the sheriff and killing everyone in sight.

In America I have come to expect this, despite the fact that America has much art to offer—make no mistake. Aaron Copland offers a vast openness, tranquility, a quiet city and a barren landscape, a harmony stripped to the bare essence and the originality of a culture only a few hundreds years old. Georgia O’Keefe, similarly, paints her distilled forms, so highly original, in contrasts, again reaching the essence within.

Yet here, in this beautiful city in Romania, here I expect the music to match the Old World tradition of the place. But the music I hear around me played in most public places is downright violent and devoid of better values. One can argue that art need not be pleasant. (I will leave the debating to those interested in politics, a topic where debates are equally ineffective).

Is this Old World doing its time, having to suffer, to join America in a vastly superior new way of life in terms of freedom? Does freedom only allow us to seek after violence? Must the great old traditions go along with the atrocities of more modern cultures, or can they not cherish the noble parts of our Western civilization?

Something inside me, however, tells me that the essence of beauty is good for us, that too much violence is bad. I feel this.

As I’m leaving the hotel, and hear the lyrics of violence, I hear something different—utterly different, profoundly different.

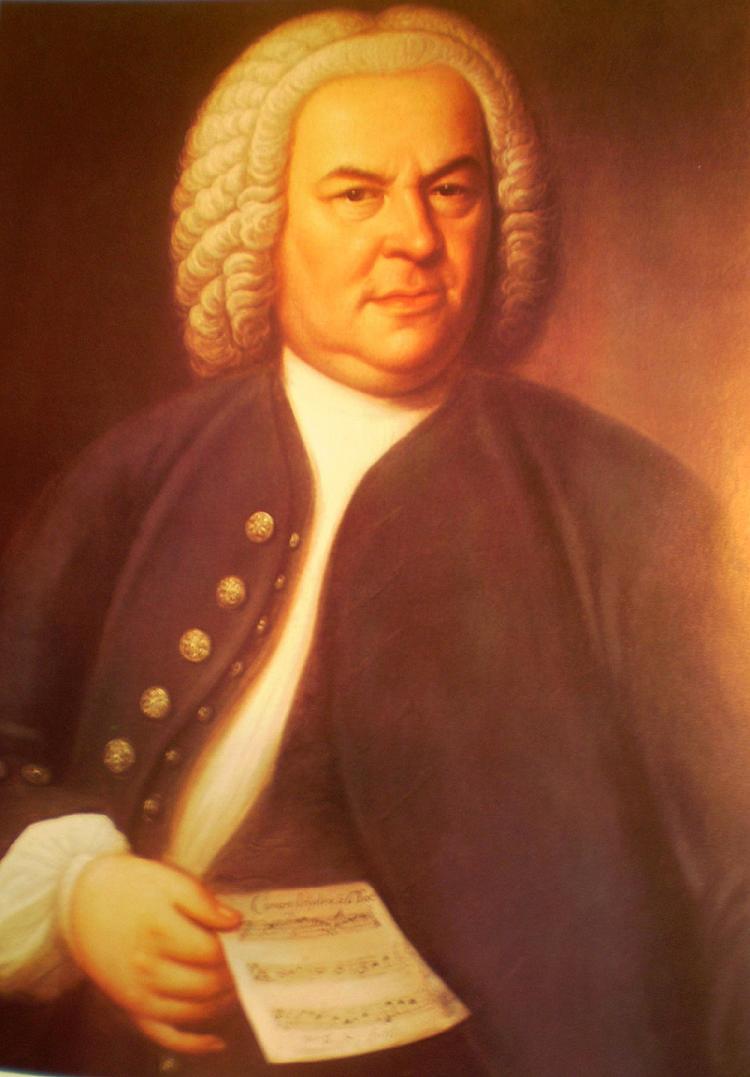

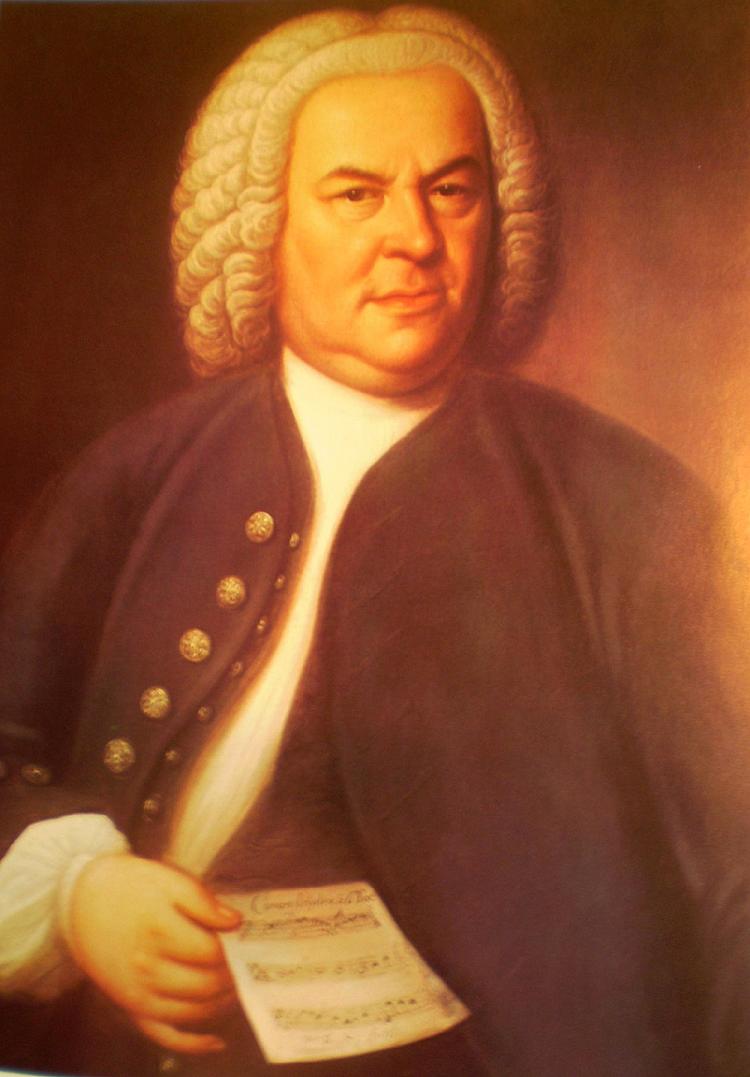

I hear in the distance, perhaps a quarter mile away, the auditory perfume of the master of all. Is it my imagination? Do I hear Bach?

As I near the town square in lovely Cluj-Napoca, Romania, I am awed by the beautiful fountains in the town square where the cascading water seems choreographed to the music of J. S Bach, and the rays of sun are spread out in a spectrum of color. The suddenness of meeting Bach in such an unexpected way, moved me, reminded me—if I had any doubts—that I still love music.

I stand overwhelmed, shocked by a recognition of greatness. Oh, the great Organ Prelude of Bach! No one could ever write greater music. Such beauty was achieved by a mortal. I know that if there was a god of music, it was Bach.

I look around at the passersby. They seem to take the moment in stride, or do they? Aren’t they, too, confronted with something extraordinary? I watch as many seem to break their stride, stop, and cant their heads.

They know they are in the presence of great music. I see it. I feel a sense of respect. Some parents stop with their children, who move their little hands to the sweep of the cascading Bach prelude so beautifully choreographed.

This music is not about the low ebbs of life. It is not about staring at a gruesome highway accident. It presents none of the base qualities potentially within us. I have the feeling people know the difference.

Please don’t tell me there is no better or worse in music.

A life devoted to finding the optimal chords of beauty carries far more power than one fixed on shocking my neighbor with the cacophony of violence.

Eric Shumsky is a concert violinist and the son of famed violinist Oscar Shumsky. For more information visit www.shumskymusic.com.