To put it another way: To write a good melody is not easy. To write two or more good melodies that combine together vertically and maintain their independence is daunting.

Bach used the technique of counterpoint in every genre he wrote for: keyboard music, chamber music, orchestral, choral, and even his works for solo string instruments.

A number of years ago, while I was studying in Boston, I was talking with a composer friend of mine. We got onto the subject of Bach and the amazing structure of his compositions, and his unsurpassed mastery of counterpoint.

My friend, who at the time was a teaching assistant and now is a professor, observed, “It’s as if Bach discovered a cave full of perfect crystals, and brought them all out for the rest of us to look at them.”

Anyone who has studied Bach even a little bit knows intuitively that his imaginative description is right on the mark.

Bach’s Influence on Later Generations

In spite of the height and beauty of Bach’s achievements as the master of Baroque music, his compositions were soon forgotten by the next generation. In the Rococo period and early Classical period, counterpoint was abandoned in favor of a simpler approach of melody with harmonic accompaniment.

It was not until Haydn and Mozart were well into their careers that they rediscovered Bach’s music. They must have been astounded.

Suddenly these great composers were experimenting with the possibilities of introducing counterpoint into their compositions. You first find them trying contrapuntal passages in their chamber music, which was where they normally experimented with new ideas before using these ideas in their symphonies and bigger works.

One brilliant example is the finale of Mozart’s Jupiter symphony, with its wonderful play of counterpoint with many voices and different subjects.

Leonard Bernstein once said that Beethoven spent his entire career trying to write a good fugue and never managed it. No disrespect intended, of course, but it’s true that Beethoven did struggle and play around with counterpoint, with more or less satisfying results.

Composers of later generations were quite aware of contrapuntal issues in composition, and Gustav Mahler maintained that he used a lot of counterpoint in his symphonies. Nevertheless, one is quite aware that the rules of harmony had been stretched quite far by his day, so the combination of melodies is much freer in his works.

With the advent of atonality and 12-tone composition of the Vienna school, all the rules of harmony went out the window, so even though 20th century composers were well aware of Bach and counterpoint, the meaning of a polyphonic composition becomes completely different. It’s no problem to write a fugue if it doesn’t have to fall within strict harmonic rules, or if the composer allows himself to invent his own set of harmonic criteria.

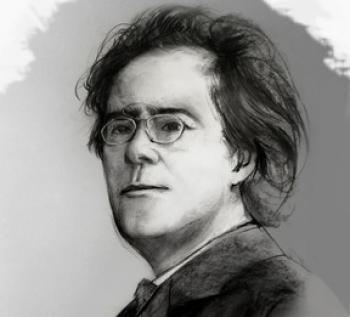

Glenn Gould: Foremost Interpreter of Bach

No article on Bach would be complete without mentioning his foremost interpreter, the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (1932–1982). Listening to his recordings of Bach is utterly fascinating. He somehow manages to make all the voices of a fugue sound independent and with great horizontal line, on a modern keyboard. I daresay his intellectual grasp of Bach went very deep.

In some ways Glenn Gould was like the Bobby Fischer (the 11th World Chess Champion) of the piano, with a meteoric rise in his career, suddenly cut off by a personal decision to retire from public performance at a young age.

But the difference between these two eccentric geniuses was that while Fischer disappeared off the face of the planet, Gould retired to the recording studio to pursue an intensive creative effort of recording the works of Bach in focused tranquility, and to work on his own compositions.

His recording of both volumes of The Well-Tempered Clavier is a monument to his dedication, and his two recordings of the Goldberg Variations, at two very different points in his life, make fascinating study in contrast.

So the greatness of J.S. Bach’s achievements stands tall to this day, unequaled by any other. The spiritual purity and beauty of his music is apparent along with the deep intellectual criteria used in its composition.

Sometimes when I play a bit of Bach, I comment to my companions, “Bach is the best,” and no one ever, ever contradicts me.

This is Part 2 of a two-part series.