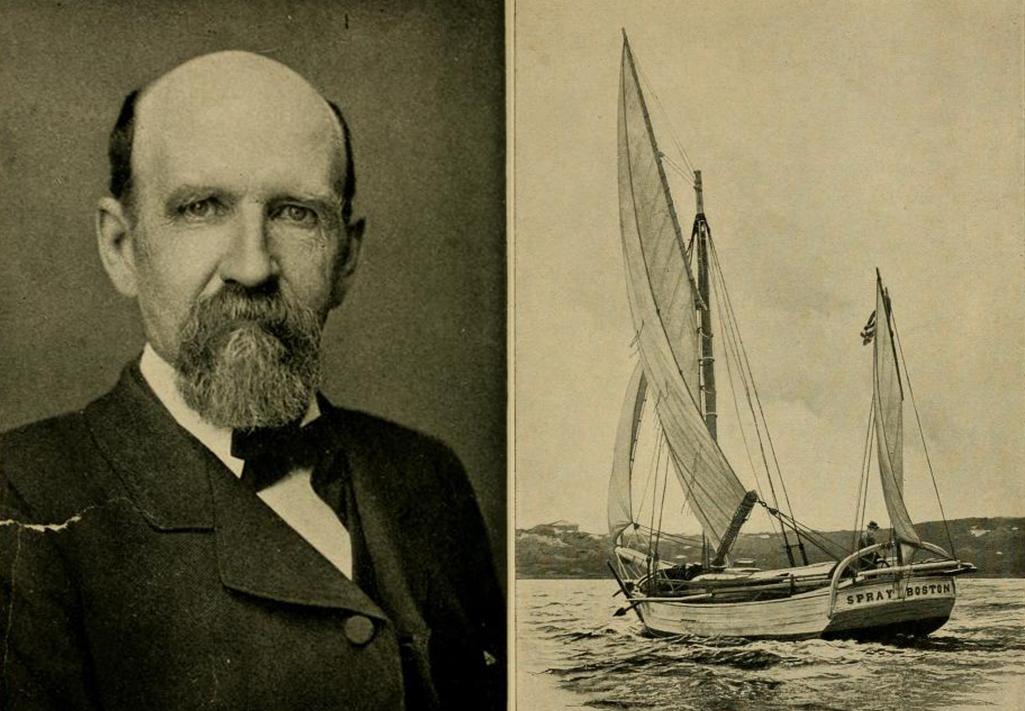

Mount Hanley sits along the coast of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. Joshua Slocum (1844–1909) was the fifth of 11 children born to John and Sarah Jane Slocum in this coastal village. His education was remedial to say the least, ending in the third grade. He did, however, learn to read and write, two skills that would serve him well later in life. His greatest skill, though, would be honed at sea. As Slocum once noted, “the wonderful sea charmed me from the first.”

Joshua Slocum's childhood school is now the Mount Hanley Schoolhouse Museum. Public Domain