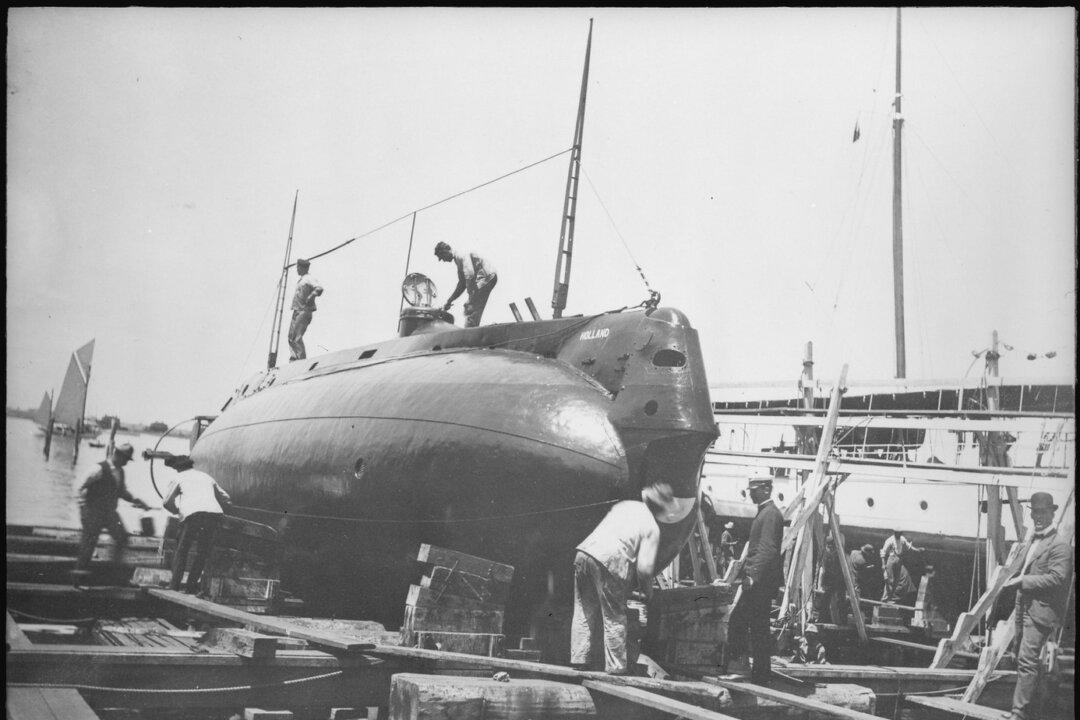

John Holland endured the Irish Potato Famine as a child and witnessed Ireland’s fight for independence. His keen mind and love of the ocean would lead to an invention that would change the course of naval warfare.

Overcoming Tragedies

John Philip Holland (1841–1914) was born the son of a coast guardsman in the village of Liscannor on the west coast of what is now the Republic of Ireland. As a boy, he was taught at St. Macreehy’s National School. According to legend, St. Macreehy killed a giant eel that had slipped from Liscannor Bay into a local cemetery to feed on corpses. Undoubtedly, Holland’s proximity to the sea inspired his life’s work.Early in Holland’s childhood, Ireland experienced the Potato Famine, followed by a cholera outbreak. Before he reached his teenage years, Holland lost two uncles, a younger brother, and his father. Along with these personal and regional tragedies, he grew up witnessing the struggle for Irish nationhood.