In these interesting times, the truth is difficult to discern. One news outlet says one thing and another says something different. Social media bombards us with opinionated echo chambers based on our most-watched videos. The fast pace of it all causes some of us to rely on headlines and memes for day-to-day truths.

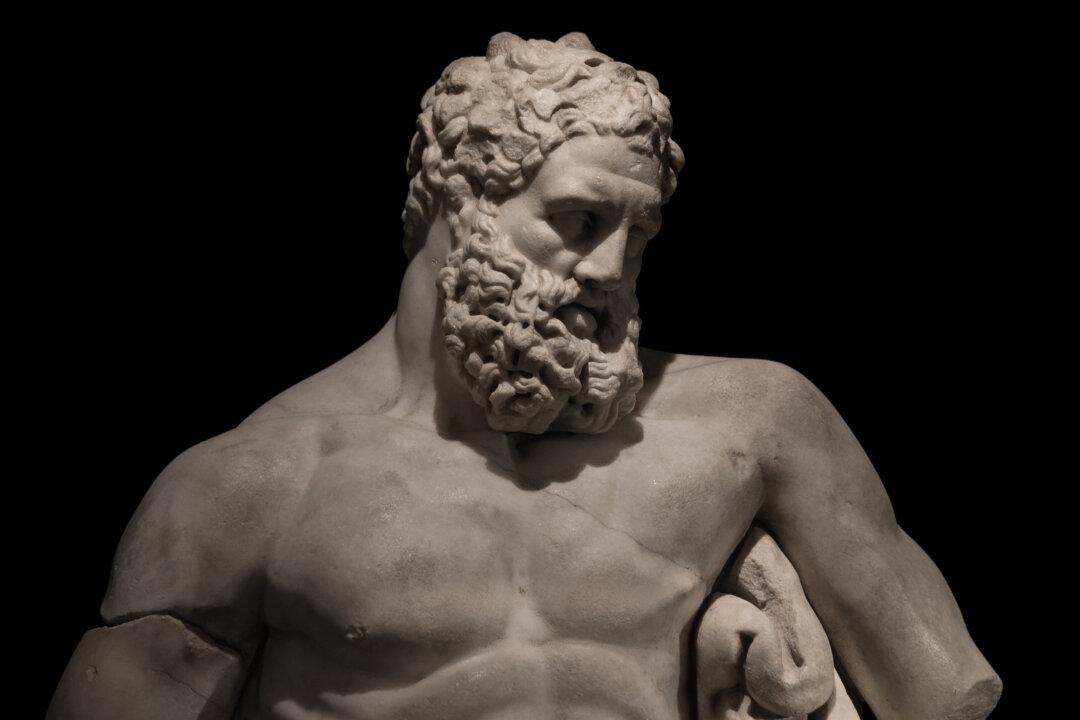

But what is truth? One of truth’s earliest and most prominent investigators was Plato, who lived about 2,500 years ago. The Greek philosopher’s ideas about truth influenced much of Western culture.