Disclaimer: This article was published in 2023. Some information may no longer be current.

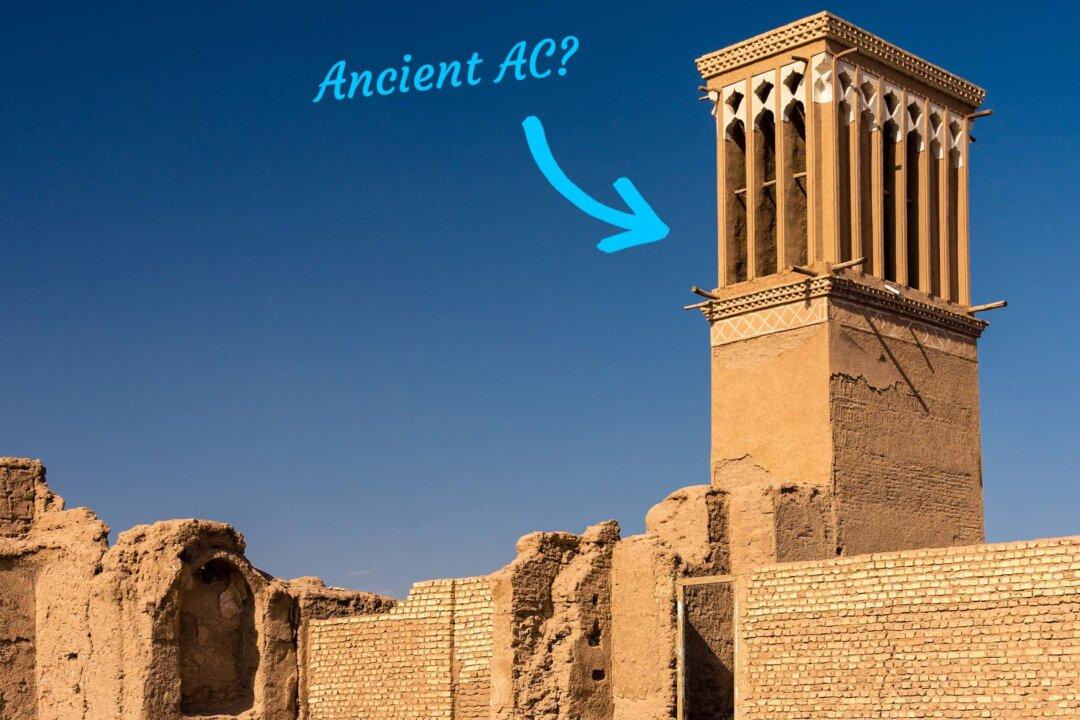

They stand towering, working noiselessly to keep the locals of Yazd cool during summer. Like square-shouldered sentinels, they break the dust-blown horizon, jutting vertically across the skyline. These were the air conditioners of ancient times.