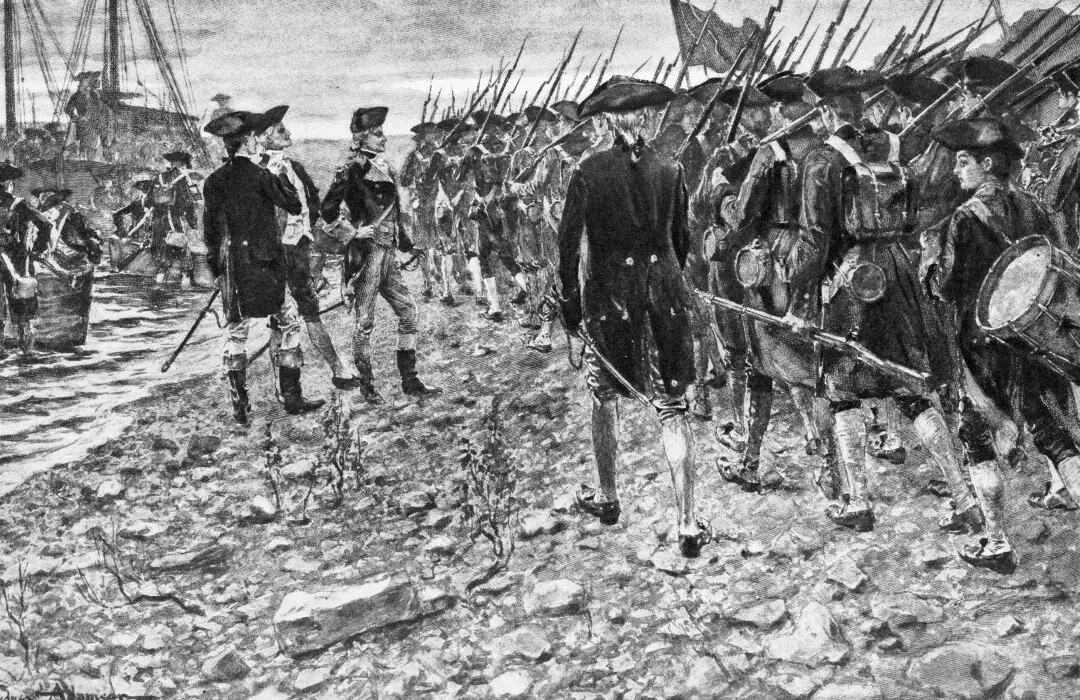

Two hundred and fifty years ago this month, the arrival of three ships in Boston Harbor carrying 342 chests of tea sparked a tense standoff between Thomas Hutchinson, the governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and a clandestine political organization known as the Sons of Liberty. This group of dedicated patriots, whose members included Samuel Adams, John Hancock, John Adams, Paul Revere, Joseph Warren, Benjamin Church, Josiah Quincy, and James Otis Jr., demanded the immediate departure of the three ships and the return of their entire tea cargo to England. In contrast, Hutchinson ordered the unloading of every chest of tea and required the payment of all import duties before any ship could depart.

When neither side yielded, and an amicable resolution seemed impossible, the Sons of Liberty executed a bold act of resistance that resulted in the destruction of the tea, sending shockwaves across two continents. Initially intended as a political and economic protest, the Boston Tea Party unexpectedly ignited a firestorm, prompting punitive actions, fostering bitter resentment, and hastening the inevitable conflict between the crown and the colonies. This escalating tension ultimately culminated in the Revolutionary War and the declaration of American Independence.