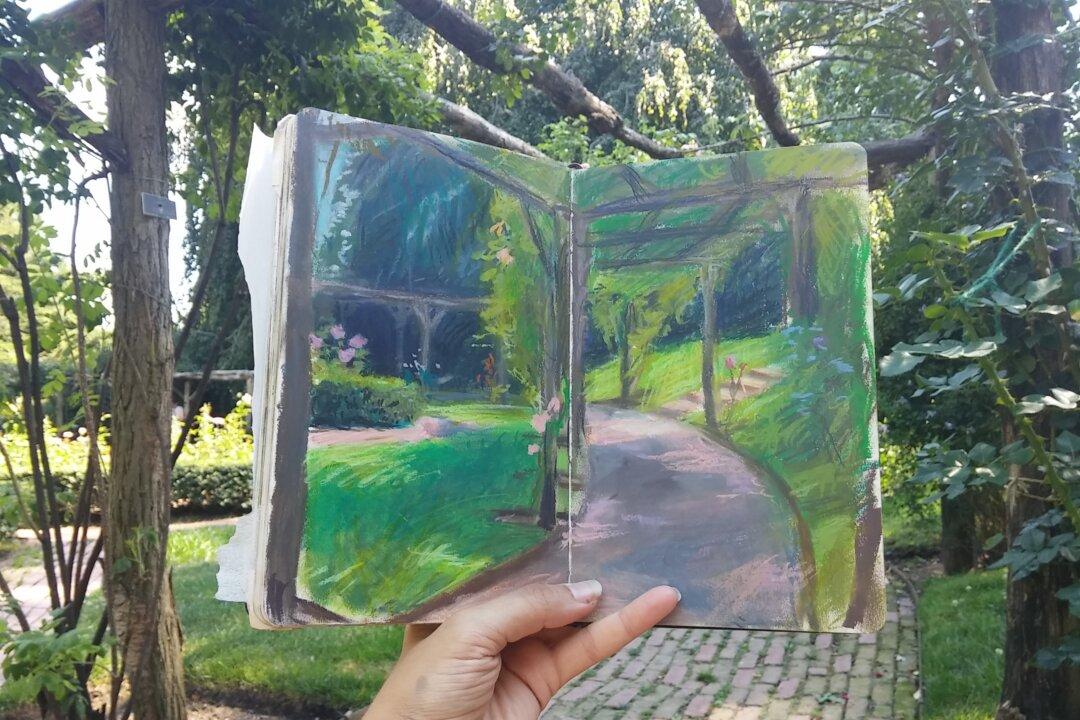

NEW YORK—Every wall in every room, hallway, and stairwell of Frederick Ross’s home is filled with stunning and captivating paintings, one right next to another, inviting deep contemplation. It would take at least two hours to take a quick glance at all of them. Ross has one of the largest private collections of 19th-century art in the country.

He founded the Art Renewal Center (ARC), a private, nonprofit educational foundation in 2000, after 23 years of collecting art that began with a small fortune he'd made in his food products company. His collection, which also includes living masters’ works, has been growing steadily, mostly by trading up, costing him very little out of pocket.