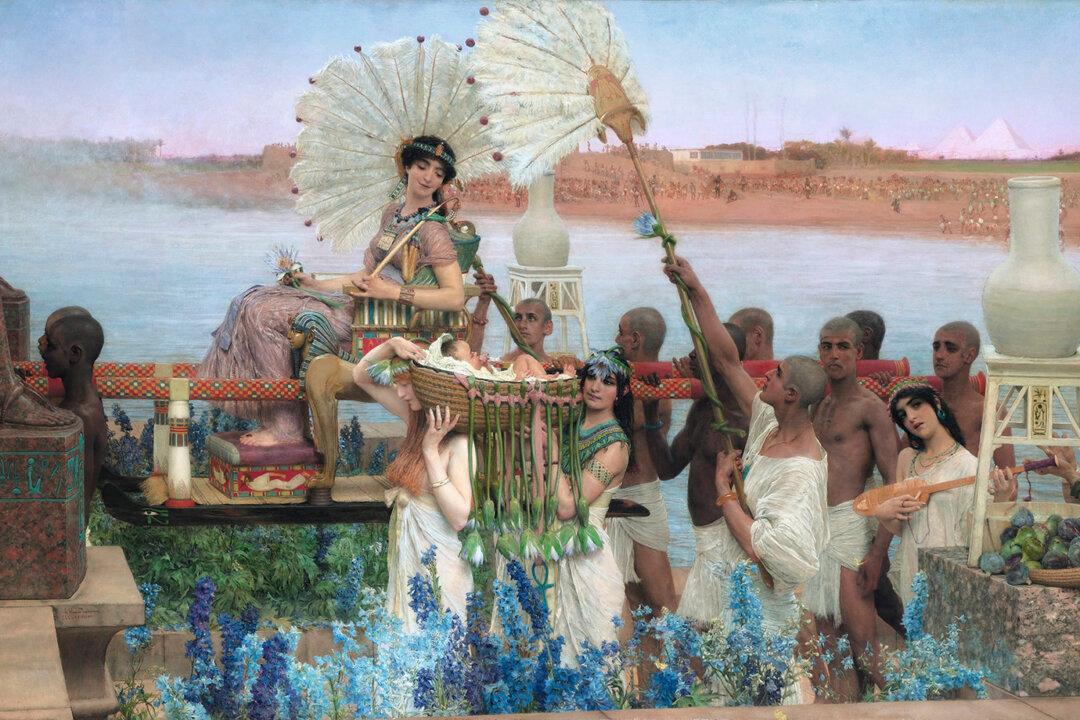

The Jewish holiday of Passover commemorates the Israelites’ liberation, led by Moses, from slavery in Egypt. The Hebrew prophet’s beginnings has been a popular theme in art history explored in paintings, drawings, frescos, prints, stained glass, and illuminated manuscripts by both Jewish and Christian artists. One of the most famous examples is the 1904 painting “The Finding of Moses” by Anglo-Dutch artist Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

The textual reference for this narrative comes from Exodus, the second book of the Bible. At the start, the Pharaoh decrees that all Jewish male newborns in Egypt be thrown into the Nile River. To avoid this fate for her son, Moses’s mother places him in the reeds by the river in a papyrus basket. The baby is found and removed from the water by none other than the king’s daughter.