The compass has a history stretching back more than 2,000 years. This tool, capable of pinpointing due north by magnetism, altered human activity forever, enabling explorers and navigators to maintain their courses to whatever destination they endeavored to reach. Navigators the world over utilized this marvel throughout the millennia, but when shipbuilders switched from wood to iron, it substantially interfered with the compass’s accuracy. The compass needed to be revolutionized, and a young American genius decided to take on the task.

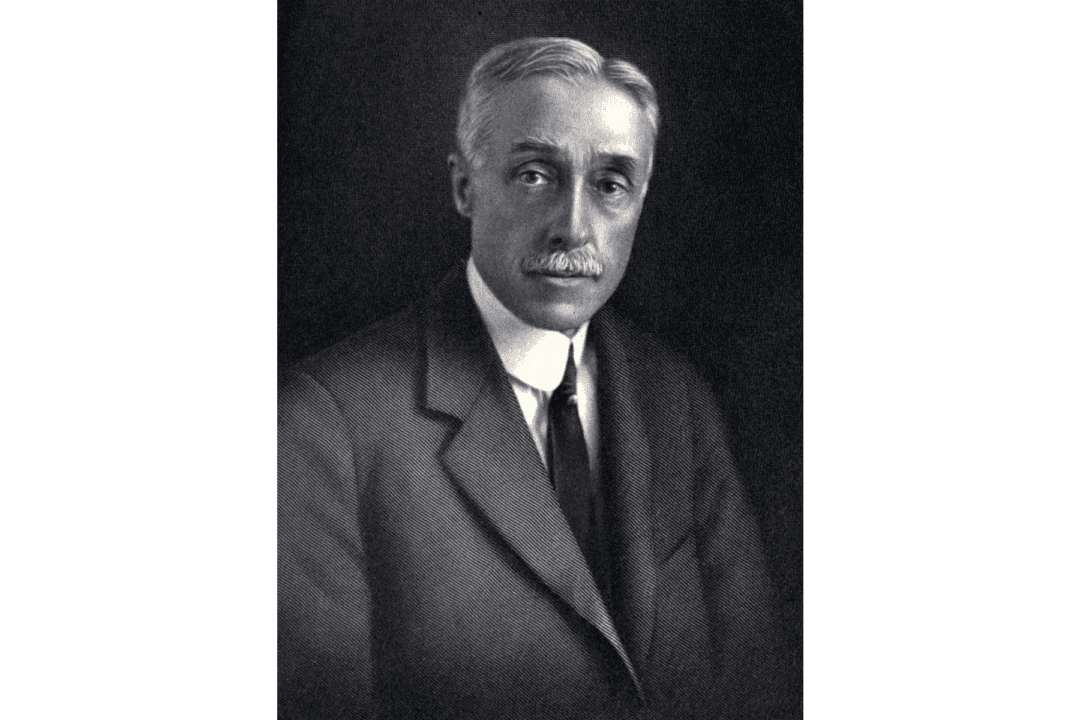

Elmer Ambrose Sperry (1860–1930) was born in Cortland in upstate New York. His father, Stephen, who was away working during the time of his birth, was given the news, which should have been a welcome announcement. The news, however, was tragic; his wife, Mary, had died from complications after giving birth. Sperry grew up without a mother and with a father who was often away working. He was sent to live on a farm with his grandparents and an aunt.