Disclaimer: This article was published in 2023. Some information may no longer be current.

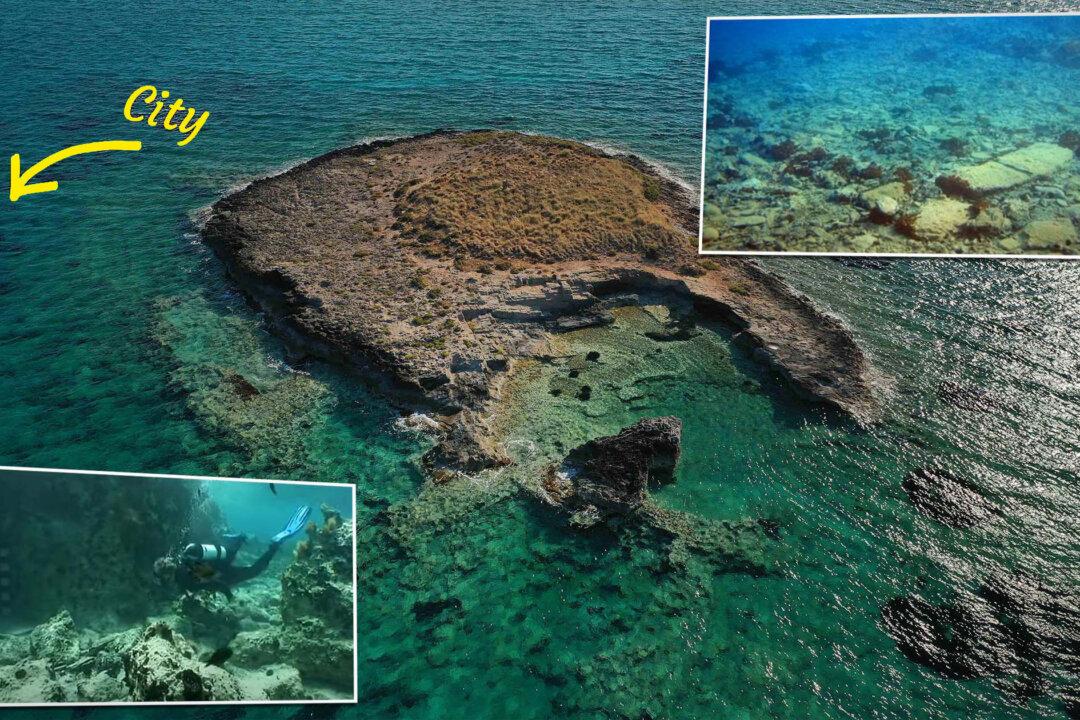

The sunken city of Pavlopetri is the stuff of myths. Just a dozen feet beneath the sea off the coast of Laconia, Greece, her ruins were thought to have originated from the Mycenaean period, but today are thought to be far older—preceding even the Bronze Age.