Buddhism started to flourish in France after the arrival of a number of Tibetan Buddhist masters who fled the Chinese army’s occupation of Tibet in the 1950s.

Today in France, there are about 800,000 Buddhists, three quarters of whom are of Asian origins, according to the Union of Buddhists.

The spiritual roots that those Tibetan masters planted take shape now in an exhibit at the Museum of Asian Arts in Nice, French Riviera. “Buddhist Treasure in the Land of Genghis Khan” spotlights Buddhist art from Mongolia and Tibet between the 15th and 18th centuries.

Prepared with the help of Jean-Paul Desroches, general curator of the Department of Chinese Art at the Musée Guimet in Paris, the exhibit contains some rare pieces that were saved when Chinese communists launched the destruction of Mongolian temples during the 30s.

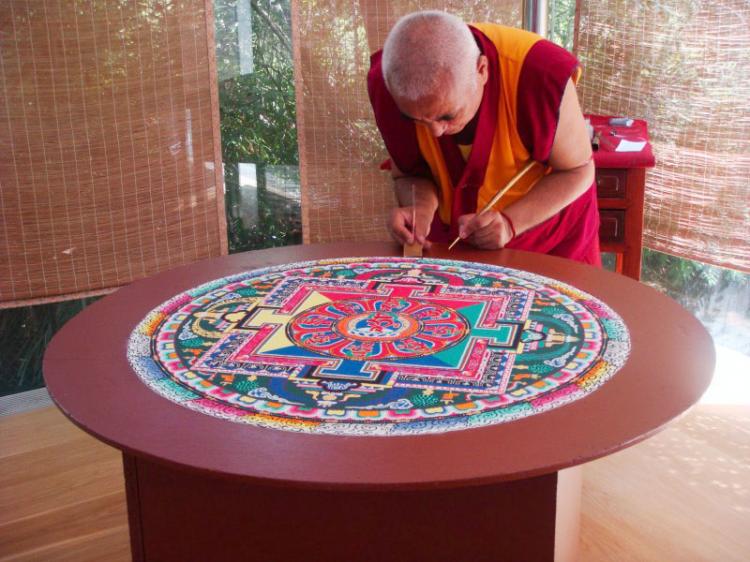

A living work of art was shown during the exhibition as well. Dorjee Sangpo, a famous Tibetan artist worked for an entire week, eight hours a day, on a Mandala Amitayus. Amitayus is the principal Buddha for overcoming the power of death and ignorance. The name Amitayus is a compound of amita (infinite) and ayus (life), and so means—he whose life is boundless.

In Sanskrit, it’s called a mandala, and Kuil-Kor in Tibetan. Mandalas are secret symbols of the tantric Buddhism tradition, and are thousands of years old. Each deity has its own mandala.

On the first day, the creation of the mandala started with a Buddhist ritual. Each mandala requires the use of millions of grains of sand. Sangpo used a chacphor (copper case) to mix sand and pigments from the Indian soil to create the colored sand for the mandala. The artist does in freehand the mandala on a table, placing sand in precise and symmetrical patterns.

Depending on the size and the number of details, a mandala could contain 16 different colors. The principal colors, blue, yellow, white, red and green represent the five subtle elements and are the principal components of the human body.

Mandalas represent the complexity of our lives. As work on it progresses, it evolves into a complex and detailed image.

At the end of the eight days, the mandala is swept into an urn and offered to the elements.

“The disappearance of the mandala represents the brittleness of life,” said Sangpo. “No matter how beautiful life could be, how much attached to it we could be, life can end naturally at anytime. This final separation helps us to understand impermanency and become more detached from our bodies and ourselves. This detachment can help us to overcome constraints, depression, and stress of life, in a easier way.”

Originally, mandalas were created with the powder of precious stones, like rubies, lapis lazuli, and more, all believed to have natural alleviating effects.

Today in France, there are about 800,000 Buddhists, three quarters of whom are of Asian origins, according to the Union of Buddhists.

The spiritual roots that those Tibetan masters planted take shape now in an exhibit at the Museum of Asian Arts in Nice, French Riviera. “Buddhist Treasure in the Land of Genghis Khan” spotlights Buddhist art from Mongolia and Tibet between the 15th and 18th centuries.

Prepared with the help of Jean-Paul Desroches, general curator of the Department of Chinese Art at the Musée Guimet in Paris, the exhibit contains some rare pieces that were saved when Chinese communists launched the destruction of Mongolian temples during the 30s.

A living work of art was shown during the exhibition as well. Dorjee Sangpo, a famous Tibetan artist worked for an entire week, eight hours a day, on a Mandala Amitayus. Amitayus is the principal Buddha for overcoming the power of death and ignorance. The name Amitayus is a compound of amita (infinite) and ayus (life), and so means—he whose life is boundless.

In Sanskrit, it’s called a mandala, and Kuil-Kor in Tibetan. Mandalas are secret symbols of the tantric Buddhism tradition, and are thousands of years old. Each deity has its own mandala.

On the first day, the creation of the mandala started with a Buddhist ritual. Each mandala requires the use of millions of grains of sand. Sangpo used a chacphor (copper case) to mix sand and pigments from the Indian soil to create the colored sand for the mandala. The artist does in freehand the mandala on a table, placing sand in precise and symmetrical patterns.

Depending on the size and the number of details, a mandala could contain 16 different colors. The principal colors, blue, yellow, white, red and green represent the five subtle elements and are the principal components of the human body.

Mandalas represent the complexity of our lives. As work on it progresses, it evolves into a complex and detailed image.

At the end of the eight days, the mandala is swept into an urn and offered to the elements.

“The disappearance of the mandala represents the brittleness of life,” said Sangpo. “No matter how beautiful life could be, how much attached to it we could be, life can end naturally at anytime. This final separation helps us to understand impermanency and become more detached from our bodies and ourselves. This detachment can help us to overcome constraints, depression, and stress of life, in a easier way.”

Originally, mandalas were created with the powder of precious stones, like rubies, lapis lazuli, and more, all believed to have natural alleviating effects.