After being raised in a household of abolitionists in the pre-Civil War era, Charlotte Forten Grimké learned at a young age to use her coveted education to make a difference. Before she even finished her schooling, she used her “power of the pen” to write anti-slavery poems.

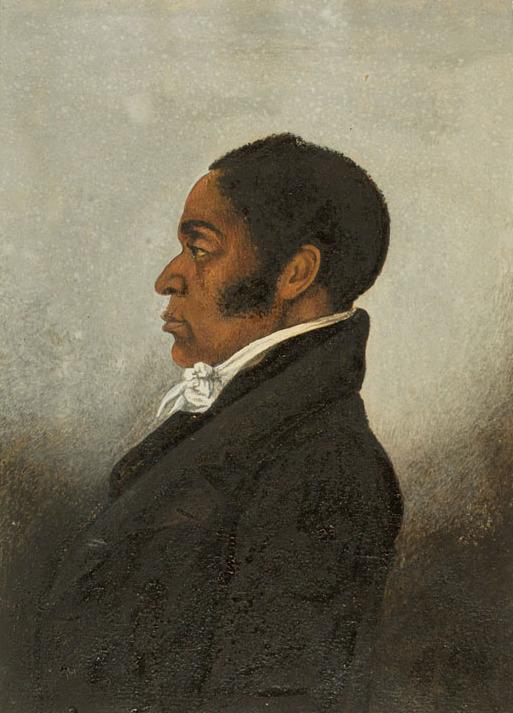

James Forten, father of Charlotte Forten Grimké. Public Domain