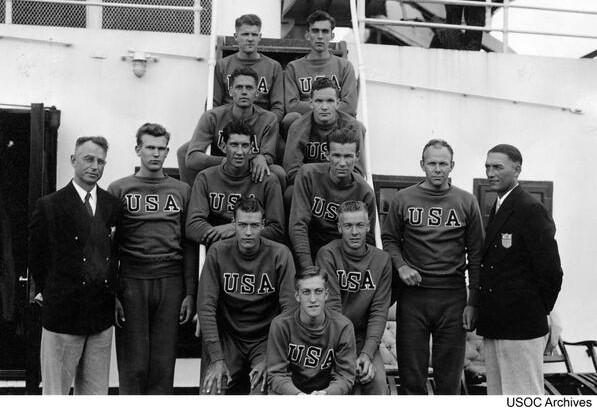

One of the best books I have read is “Boys in the Boat: Nine Americans and Their Epic Quest for Gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympics” by Daniel James Brown, an account of the American rowing team that won Gold in the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

It highlights one particularly important lesson: winning sometimes requires that one not just be better, but much better than your opponent. A competitor faces not only an opponent but an array of surrounding factors, such as an umpire, luck, and his or her own personal difficulties.