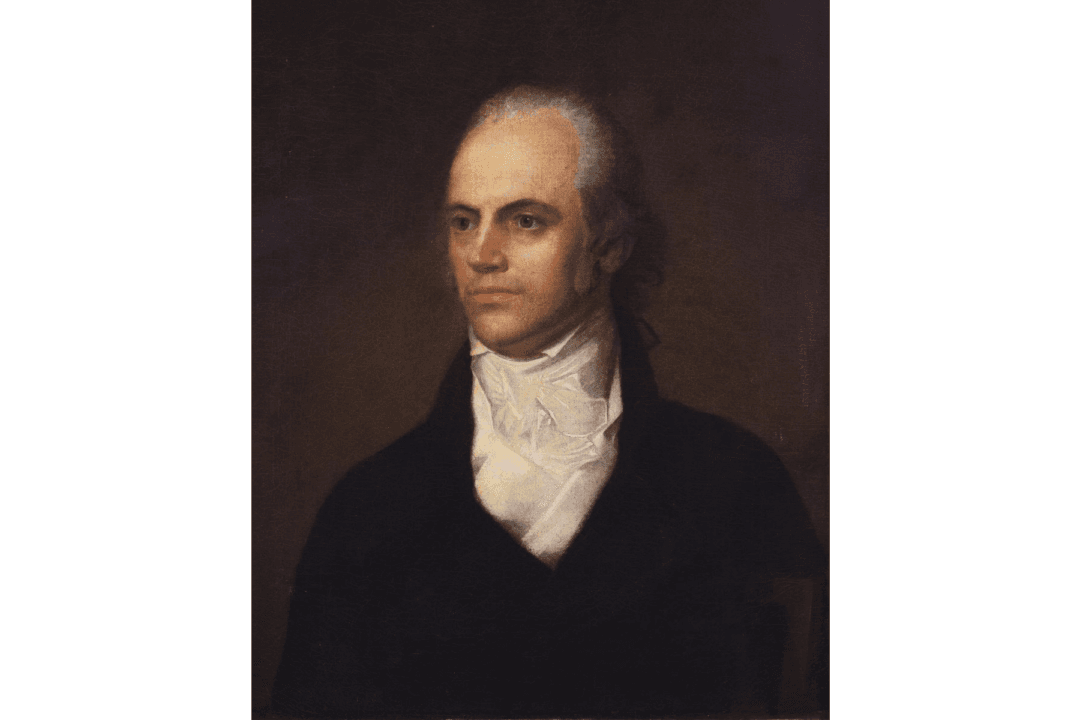

Alexander Hamilton was dead and buried, killed by a gun fired by Aaron Burr. At the height of his political power, Burr had killed Hamilton, and, much like Hamilton on the day he was shot, July 11, 1804, Burr’s political life would enter its death throes on July 12—the day Hamilton died.

Burr had witnessed a steady rise politically, from joining the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War to becoming attorney general for New York, then serving as a senator from 1791 to 1797. He was one vote shy of winning the 1800 presidential election and, therefore, had to settle for the vice presidency under Thomas Jefferson. Burr, however, had spurned too many political foes and allies alike, and, after the duel with Hamilton, his rise had come to an end.