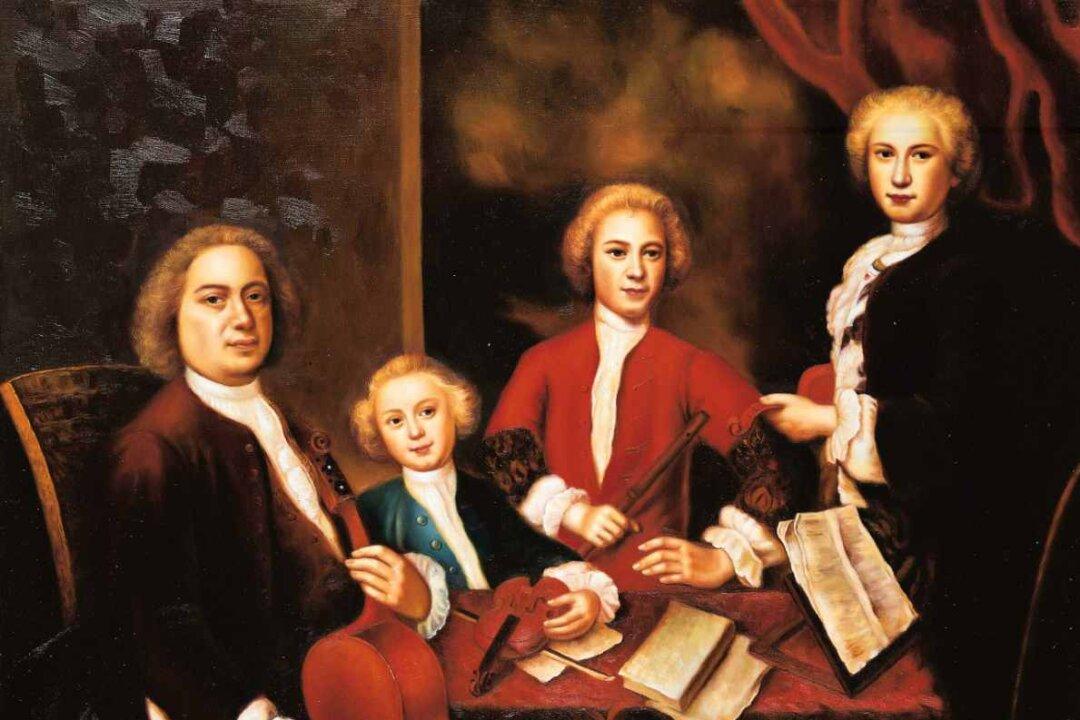

“Bach ... needed no audience. He wrote for himself alone.”

So an astonished Mozart tells Baron Gottfried van Swieten after being introduced to “The Art of Fugue.”

“Bach ... needed no audience. He wrote for himself alone.”

So an astonished Mozart tells Baron Gottfried van Swieten after being introduced to “The Art of Fugue.”