Boise, Idaho—The first thing that strikes me about chef Dan Ansotegui’s cooking is the colors. I’m staring at an aromatic quartet of vibrantly red roasted piquillo peppers, stuffed with a creamy spinach béchamel, floating in an orange and red pepper sauce and topped with green parsley.

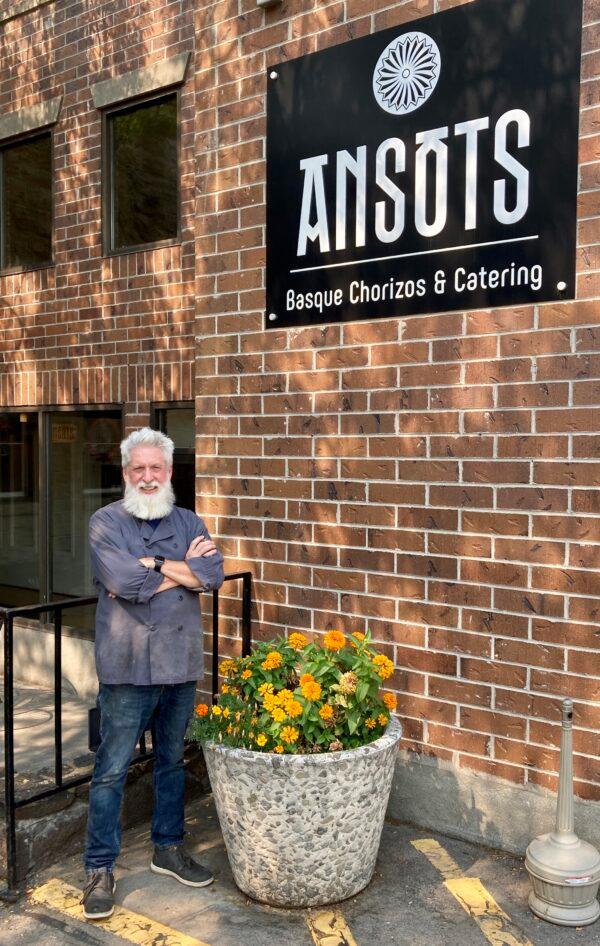

Dan Ansotegui stands outside Ansots restaurant in Boise, Idaho. Joseph A. Lieberman