Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) wrote “Aida” on commission for the opening of the opera house in Cairo in 1871. Combining spectacle with a tragic love story, it is one of the most popular operas.

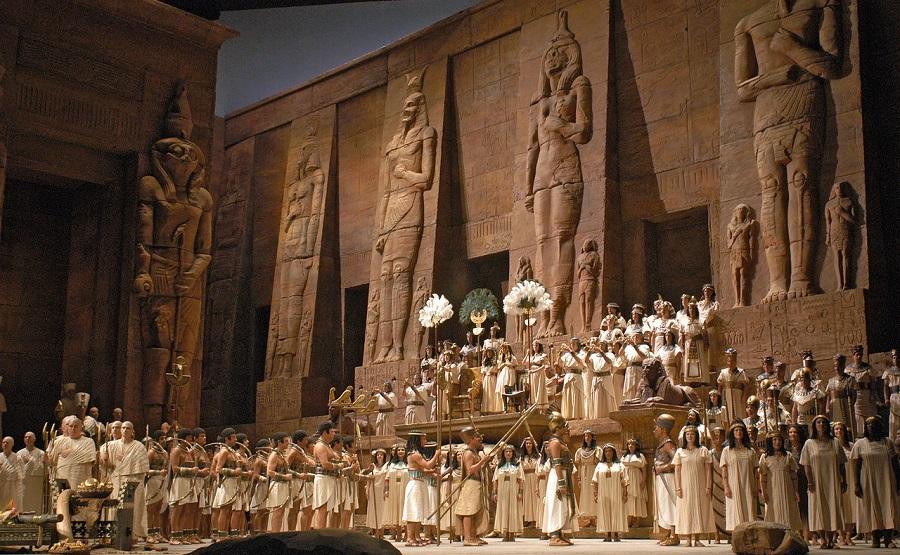

The Met’s revival of Sonja Frisell’s 1988 production is visually impressive and musically stirring. As drama, it is somewhat inert.

The plot of “Aida” was created by Auguste Mariette, an archaeologist who was the founder of the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, and Camille du Locle, who had worked with Verdi on “Don Carlo.” Antonio Ghislanzoni wrote the libretto.

The Plot

“Aida,” set in ancient Egypt, is a love triangle. The Egyptian general Radamès is in love with Aida, an Ethiopian slave. She is the daughter of the Ethiopian king, Amonasro. Aida, in turn, is the servant of the Egyptian princess Amneris, who is also smitten with Radamès.

When it is announced that the Ethiopians are about to attack, the Egyptian king names Radamès as leader of the army. Aida is conflicted between her feelings for Radamès and her patriotism for her native country.

When Act 2 begins, Egypt has defeated the Ethiopians. Amneris tricks Aida into revealing her love for Radamès by initially telling her that he has been killed in battle.

During an immense celebration for the victorious army, Aida spots her father, Amonasro, among the prisoners. He urges her to keep his identity secret.

As a reward for Radamès’s success, the Egyptian king presents him with the hand of Amneris in marriage.

In Act 3, Amonasro convinces Aida to find out from Radamès the route the Egyptians plan to take to invade Ethiopia. Amonasro hides while the lovers meet and plan to run away together.

The Ethiopian king reveals himself right after Radamès informs Aida of his army’s plans. However, Amneris and the Egyptian high priest Ramfis then step out of the darkness. Aida and Amonasro manage to escape but Radamès surrenders.

The last act starts with Radamès declining to renounce Aida or to defend himself against the charge of treason. Once he is sentenced to be buried alive, Amneris has a change of heart. She tries to get the priests to grant leniency but fails. Aida sneaks into the tomb so she can die along with Radamès.