Most of us will recognize the portrait of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s mother, Anna, that he painted. It’s one of the most celebrated American paintings, and the first work by an American artist that the French government bought. Yet it’s a portrait that nearly never came to be.

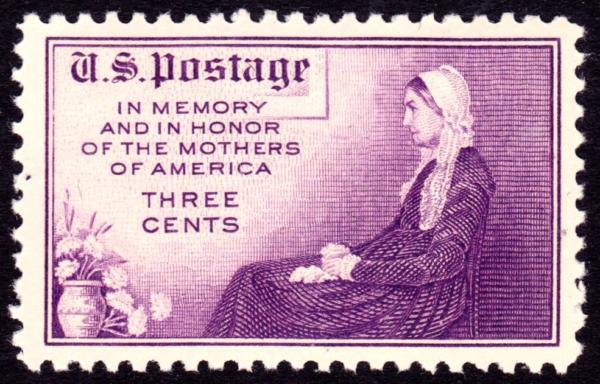

As one of the nation's most loved paintings, "Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1" has been reproduced many times, from a poster urging men to enlist with the Irish Canadian Rangers to the 1934 postage stamp "In memory and in honor of the mothers of America." Public Domain