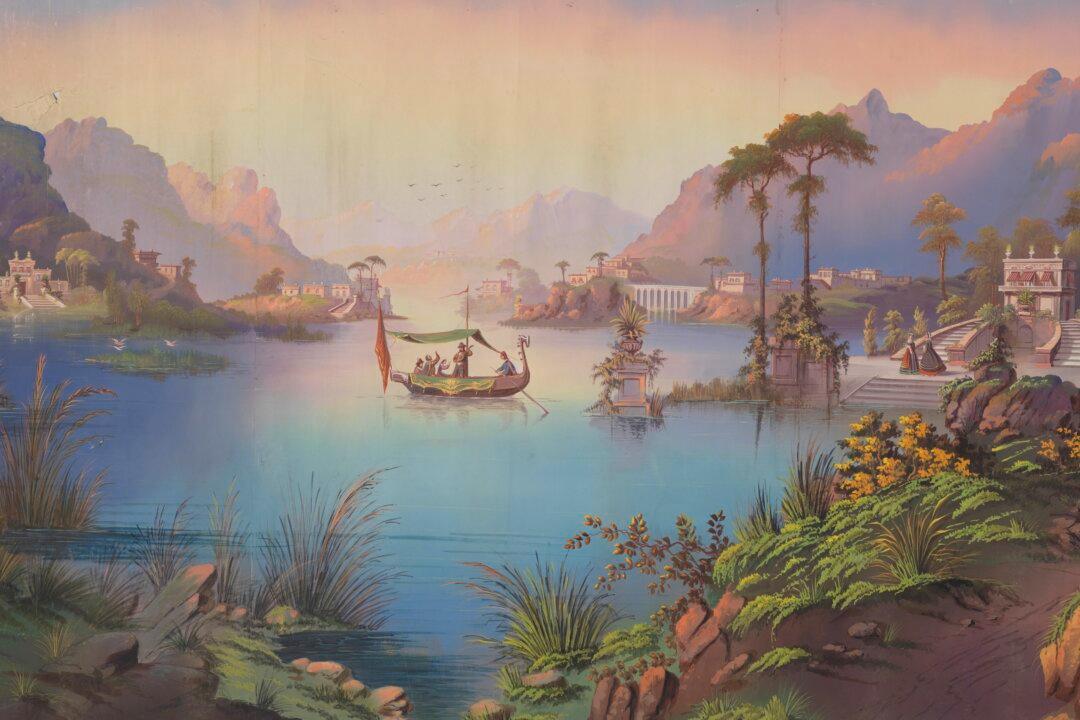

Six rolls of vibrant, exotic-style wallpaper totaling 190 feet, 3 1/2 inches once wowed 19th-century Europeans, but not as wallpaper. When the Rijks Museum’s curators began searching their collections of large works on paper for the museum’s “XXL Paper—Big, Bigger, Biggest!” exhibition, they discovered that those six rolls were part of one work of moving images, titled the “Reuzen-Cyclorama” (giant cyclorama).

Before movies, people paid to see moving panoramic paintings (called moving cycloramas in some parts of the world). A wooden frame held the long roll of painted paper that was wrapped between two wooden poles, allowing the scenes to be slowly revealed within the frame. Small holes at the top of the paper show how the museum’s painting once hung on a wooden frame. Even though the Rijks Museum’s painting is huge, it’s just one small fragment of the nearly one-mile-long moving cyclorama.