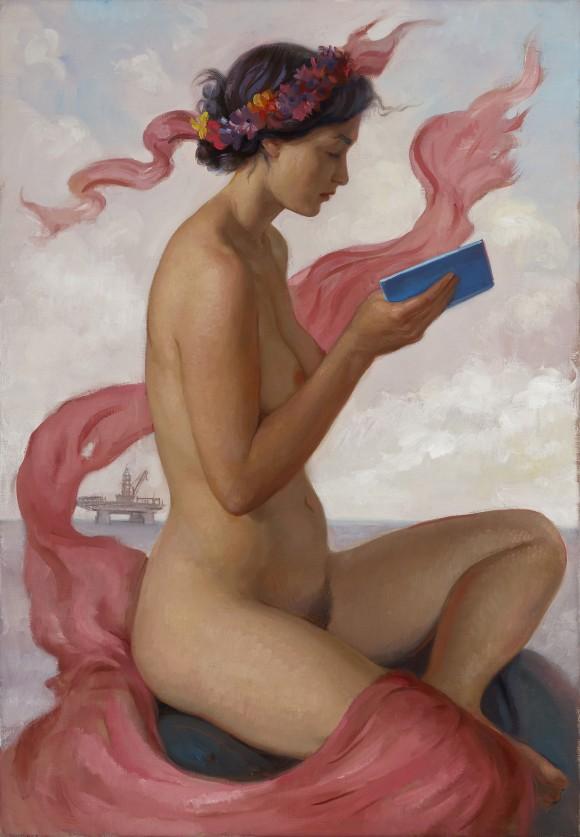

NEW YORK—A woman sitting on a rock by the sea reads a royal blue book. A pink stole draped over her knee swirls up around her nude figure. She maintains a wonderfully serene, self-contained expression. Hinting at the use of earth’s resources, the stole, as it flows past the small of her back, frames an oil platform in the distant background, in Patricia Watwood’s painting “Pink Sibyl.”

The name Sibyl comes from the ancient Greek word Sibylla, meaning prophetess—a woman who interprets divine messages. Like the many Sibyls as well as other female mythic figures she paints in contemporary settings, Watwood takes on the role of the artist as a messenger. She uses myths and creates allegories. Her paintings tell stories.

"Pink Sibyl," 2015, by Patricia Watwood. Oil on linen, 20 inches by 14 inches. Courtesy of Patricia Watwood